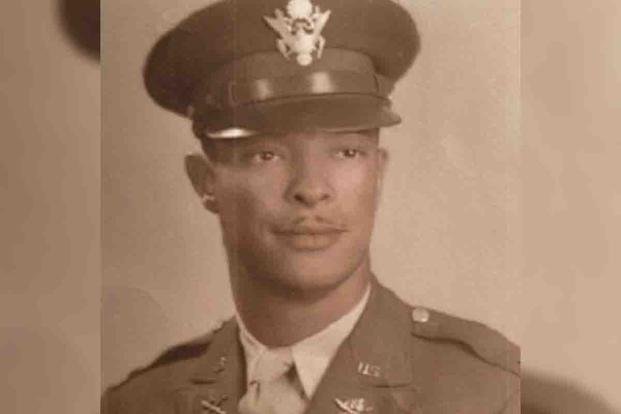

The day after Christmas in 1944, the 92nd Infantry Division was in Italy fighting the Nazis in the Serchio River Valley. Among them was Lt. John R. Fox, a forward observer with the 598th Artillery Battalion. Positioned on the second floor of a house in the village of Sommocolonia, Fox watched as the Americans abandoned the town in the face of overwhelming German numbers.

As he called in artillery fire, he realized his position in the house was about to be overrun. So he called for a strike on his own coordinates. He told the artillery to give the enemy hell. Fox was killed in the barrage, along with 100 enemy troops. He wouldn't receive recognition for his sacrifice until 1982, when he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Decades after Fox gave his life in a small Italian village, the U.S. government decided he was denied because of systemic racism in the awards process.

Italy capitulated to the Allies and turned on its former Axis partner, Germany, in 1943. Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini was overthrown and later killed, and Hitler's forces occupied the land it held. Rome fell to the Allies that same year. By December 1944, American forces were pushing the Germans back into northern Italy.

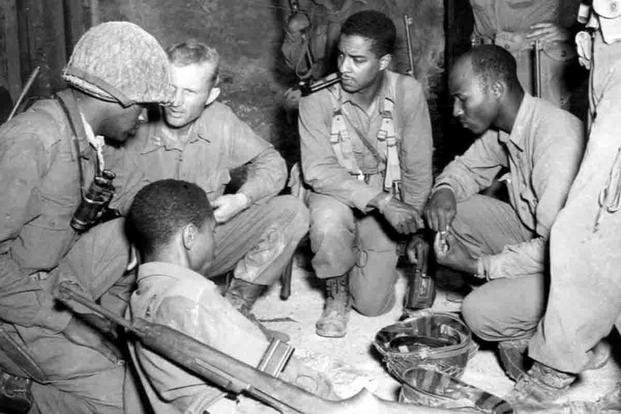

The 92nd Infantry Division, also known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was a segregated unit sent to the Italian Front in 1944. It was the only all-Black infantry division to fight in combat in Europe during World War II. Fox and his company arrived in Italy on Dec. 9, 1944

On Dec. 23, Fox volunteered to head an artillery observation post in the contested village of Sommocolonia, held by just 70 Black soldiers and 25 Italian partisans. It was supposed to be a four-day mission, but Fox and the Americans had no clue the Germans were preparing to go on the offensive. Operation Wintergewitter (Winter Storm) was specifically designed to target the newly arrived and inexperienced 92nd Infantry.

Three days after Fox set up his position on the second story of a house, the Germans significantly increased their mortar attacks on the American positions in Sommocolonia. Early that morning, the 92nd took small arms fire and artillery barrages for the first time ever.

A relentless series of attacks from the German 14th army quickly followed, and the Germans would not be taking any Black prisoners. Although the Americans were ordered to hold the village at all costs, the 92nd could not hold against the swarms of enemy troops coming at it. Fox ordered his men to retreat with the rest of the Americans.

As they made their getaway, Fox continued to send coordinates to the artillery supporting the American defense of the village. The coordinates kept getting closer until he finally ordered an artillery strike on his own position.

The voice on the other end of the radio was Otis Zachary, a good friend of Fox's. He warned Fox that he was calling in an attack on himself, to which Fox replied: "Fire It! There's more of them than there are of us. Give them hell!"

Along with the 29-year-old Fox, the artillery killed an estimated 100 German troops and gave the Americans enough time to conduct an orderly retreat and help Italian civilians escape the carnage. The German offensive was also delayed. The 92nd reorganized itself and launched a counterattack, taking the village again on Jan. 1, 1945.

Despite his sacrifice, Fox wasn't recommended for any medal at the time of his death. His remains were sent home and buried in Whitman, Massachusetts. That was the end of Fox's story until 1982, when Fox received the Distinguished Service Cross after the Pentagon began to review the records of Black soldiers.

But that's not the end of the story, either.

Not a single Black soldier received the Medal of Honor during World War II, and Black veterans groups wanted to know why. In 1993, President Bill Clinton took office and ordered the Pentagon to find out. Although no direct evidence of discrimination was found, it noted that systemic racism permeated the culture of the war department.

The Army asked North Carolina's Shaw University to investigate the Army's nominations and awards processes at the time. In 1996, Shaw recommended that 10 Black soldiers be considered to receive the Medal of Honor for their actions in World War II. Fox was one of those 10 soldiers, and one of seven to be approved for an upgrade.

In 1997, Clinton presented Fox's Medal of Honor to his widow, Arlene.

''I think it's more than just what it means to this family," Arlene Fox said during the presentation ceremony. "I think it sends a message to all, like a little wakeup call, that when a man does his duty, his color isn't important.''

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.