Jackie Robinson was one of 1.2 million Black Americans to be drafted during World War II, but the Army he entered looked very different from the Army of today.

The U.S. military has always adapted to social change faster than the rest of the United States. President Harry S. Truman signed the order desegregating the military in July 1948. Almost four years to the day before, a future Major League Baseball Hall of Famer was facing a court-martial for six violations of the Articles of War.

All because Robinson refused to move to the back of a bus.

At the time, he was not the Jackie Robinson who broke MLB’s color barrier and the league record for stolen bases. When he was drafted into the Army in 1942, he had just arrived in Los Angeles from Honolulu to play football for the LA Bulldogs. The Imperial Japanese Navy struck Pearl Harbor the previous December and the United States entered the war.

Robinson lettered in baseball while he was a student at UCLA in the late 1930s, along with basketball, football and track. Baseball, he said, was actually his "worst sport."

He was sent to Fort Riley, Kansas, where he applied to Officer Candidate School. There were some integrated facilities for this kind of training, but few Black candidates could access them. Black soldiers, regardless of rank, still face verbal and physical harassment on the base. Base facilities were also far from equal.

Since Robinson was a football star at the time, he was expected to play on the Fort Riley football team, but by this time, playing baseball had become his new goal. The post’s baseball team was fully segregated, however, and there was no team for Black soldiers. The post commander ordered him to sign up for football.

It wasn't long before Lt. Robinson, a cavalry officer, finally found himself in a tank battalion, this time at what was later known as Fort Hood in Texas, and which today is Fort Cavazos.

To Robinson and other Black officers, Fort Hood was the end-all, be-all of segregation. It reportedly had facilities marked for use by not just "Whites" and "Colored" only, but entirely separate places marked for use by "Mexicans."

Still, as a young officer, the future Hall of Famer showed promise and was selected to go overseas with the 761st Tank Battalion. Before he could deploy, he had to have an old football injury evaluated at the post hospital. He hopped on a bus to make his way there and saw the spouse of a fellow Black officer, so he sat to talk with her.

At this time, military buses on military posts were already desegregated, so when Robinson sat down in the middle of the row of seats, there should have been no problem. Yet, despite the new regulation, the bus driver wanted to enforce the state law -- segregation -- and ordered Robinson to the back of the bus.

Robinson explained the regulation to the driver and refused to move. The driver promised he would give the officer hell when they arrived at a transfer station -- and that's exactly what happened.

The station dispatcher and the driver called Robinson a flurry of racially charged names before military police arrived on the scene. Robinson and a white private were taken to the MP station for questioning. While there, he received more verbal flak from the commanding officer and the commander's secretary.

Robinson was charged with insubordination, disturbing the peace, conduct unbecoming an officer, insulting a civilian woman and refusing to obey a lawful order of a superior officer. His commander, Col. Paul Bates, didn't believe any of it. He thought the MPs were racially motivated in their investigation and refused to sign the charges.

The Army simply transferred Robinson to a commander who would sign the charges.

Official proceedings in the case of United States v. 2nd Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson, 0-10315861, Cavalry, Company C, 758th Tank Battalion, began on Aug. 2, 1944. His lawyers proved that Robinson was provoked by the use of racial slurs and that his charges had nothing to do with the Articles of War.

He wrote about the situation in his 1972 autobiography, "I Never Had It Made."

"This was... a situation in which a few individuals sought to vent their bigotry on a Negro they considered 'uppity' because he had the audacity to exercise rights that belonged to him as an American and a Soldier."

Robinson was found not guilty by a panel of nine Army officers. His arrest didn't provoke acts of civil (or military) disobedience the way Rosa Parks' arrest in Alabama would in 1955. It did keep Robinson from deploying to Europe with the 761st, where they fought Nazi forces during the Battle of the Bulge and in the Rhineland.

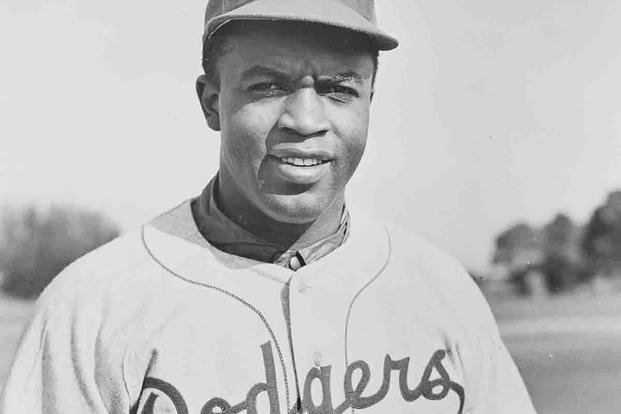

Lt. Robinson left the Army that November, returning to the LA Bulldogs. With his sights still set on baseball, he joined the Negro League's Kansas City Monarchs in 1945. His road to breaking down the color barrier began that same year, when the Brooklyn Dodgers signed him to their minor-league team, the Montreal Royals.

In 1947, the Dodgers called Robinson up to the major leagues, finally challenging the barrier of white supremacy in America's national pastime. Robinson’s taking his position on the field in Brooklyn was the beginning of the end of segregation in the United States.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.