These days, airlines can't get enough military pilots. They recruit so heavily from the military, using huge pay bumps and preferential basing, that the military has a hard time retaining enough pilots in some areas.

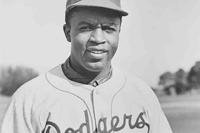

When Marlon Green applied to fly for Continental Airlines in 1957, they were excited to have him until they learned he was a Black pilot. It would take six years and a Supreme Court case before he actually started flying for Continental.

Green was a pilot with the United States Air Force, who flew B-26 Marauder Bombers and SA-16 Albatross seaplanes while at Johnson Air Base in Japan. At age 28, and still flying for the USAF, he read about a pledge from commercial airlines, which promised not to discriminate against hiring candidates based on their race.

He decided he would go on leave back to the U.S. and apply to be a pilot for Continental Airlines. He had 3,000 flight hours under his belt and was a military-trained pilot. Even in those days, flying commercial was a much better payday for pilots than the military was. After nine years in the Air Force, Green was ready for a change.

When he arrived in the U.S., he applied for work at every major airline that existed, along with some of the smaller ones. The pledge wasn't worth a damn. The only interview he received was with Continental, and it was only because he'd left the box for "race" blank. He also did not submit a photo, for which the company also asked.

Six applicants arrived at Continental Airlines to jockey for four flying positions. Green was the only Black man among them, but he was the only one with more than 1,000 flying hours in multi-engine aircraft. When Green was not hired and four lesser-experienced White pilots were, he took action.

Colorado, where Continental was based at the time, had just passed the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act of 1957, which allowed Green to appeal the hiring decision to a commission on discrimination in the state. The commission found that Green had been discriminated against and ordered the airline to begin his flight training.

Continental fought back and appealed the decision, which was first reversed in a district court. The Colorado Supreme Court upheld the reversal, so the commission took it all the way to the Supreme Court.

By that time, the dispute, "Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Continental Airlines, Inc.," had become less about the details of the case, and more about the application of the law and interpretation of past decisions. Green had been discriminated against, but did the Colorado commission have the right to do anything about it?

The airline argued that the state's anti-discrimination law extending to the flight crew of an interstate carrier would impose an undue economic burden on airlines. As hiring laws in different states have different restrictions, it might confuse how an airline would hire pilots and crew in different states, the airline contended.

The Supreme Court was "not convinced," according to the official decision. To support its argument, the airline cited cases that had no mention of hiring legislation in any state, and the justices told it as much. The court also held that laws or rulings that allowed discrimination in any manner violated the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment and the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In 1963, the anti-discrimination commission's ruling was upheld, as was its determination that Green had been the victim of Continental Airlines' racial discrimination. He was hired and trained, as the commission ordered, in 1964.

Green began flying passengers for Continental Airlines in 1965 but was not the first Black man to fly for a major commercial airline. As the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission fought in the Supreme Court, David E. Harris was finishing up his own Air Force career. He was hired by American Airlines in 1964, becoming the first Black pilot for a major U.S. passenger airline.

When Harris told American Airlines he was Black, the interviewer responded with, "This is American Airlines and we don't care if you're black, white or chartreuse; we only want to know, can you fly the plane?" avoiding a lengthy court battle.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.