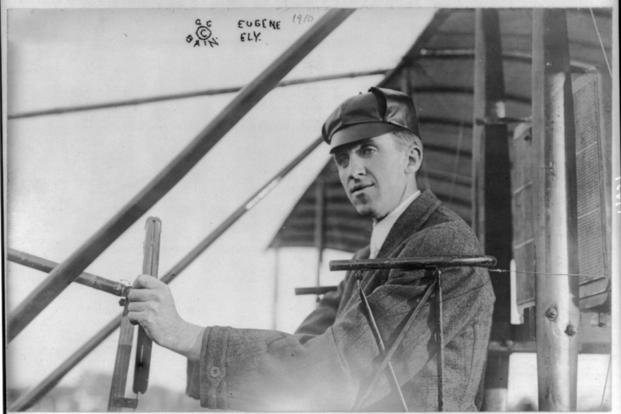

Eugene Ely did not become the godfather of naval aviation without having a high tolerance for fear.

During a time in U.S. history when inherent risks were baked into various modes of transportation, Ely plowed ahead, becoming one of the first race-car drivers in America and teaching himself to fly only after first crashing a plane.

Ely’s daring and fortitude paid off, and he eventually ushered in the age of U.S. naval aviation by successfully taking off from a U.S. Navy warship in Virginia on Nov. 14, 1910.

"Aerial navigation proved today that it is a factor which must be dealt with in the naval tactics of the world's future," an Indianapolis Star reporter wrote at the time.

While Ely was behind the controls, Capt. Washington I. Chambers was largely responsible for championing the historic flight. While the U.S. military had dabbled with launching hot air balloons from watercraft during the Civil War, Chambers felt strongly that the Navy needed its own robust aviation component when few others in the service saw the upside of such an investment.

Believing a flight demonstration might sway top brass, Chambers started pitching the idea to various aviators. The Wright Brothers declined his offer to fly one of their planes off a battleship's deck, but Chambers found a potential taker when he met Ely and aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss at a flying meet in New York in October 1910.

Although their motivations for the endeavor differed, the pairing proved a perfect match. While Chambers saw the attempt as a way to show how airplanes could benefit naval operations, Curtiss' motivations were purely financial; an aircraft manufacturer, he viewed partnering with the Navy as free publicity for his business.

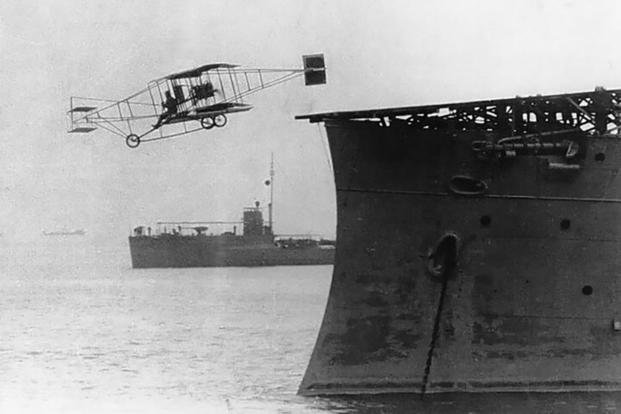

The three struck a deal, and construction began immediately on an 85-foot-long, 24-foot-wide flight deck that would be affixed to the bow of the naval cruiser USS Birmingham. Under the flight plans, Ely's Curtiss Model D pusher biplane was supposed to be launched while the Birmingham was underway in Chesapeake Bay. Once airborne, Ely was instructed to circle the harbor before returning to the Norfolk Navy Yard, a distance of about 50 miles.

It was foggy, rainy and windy that day, though, and the Birmingham was forced to drop anchor. After a three-hour delay, the weather cleared and, growing impatient, Ely decided to take off with the warship still not moving. That inertia deprived the plane of benefiting from any lift produced by wind passing over the deck, which was less than 40 feet above the bay.

The plane took off but hit the water, damaging its propeller. Increasing the degree of difficulty, Ely's vision also was obscured for a bit after saltwater sprayed across his goggles. Thankfully, the aircraft had been equipped with pontoon floats, so Ely was able to get the compromised plane in the air, if only for a short time. After proving a plane could take off from a ship, Ely searched for the nearest patch of dry land and touched down, ending the five-minute flight after less than three miles.

While the flight did not last as long as intended, the powers-that-be, including Navy Secretary George Meyer, were impressed, and Meyer called for more funding to study the potential of naval aviation.

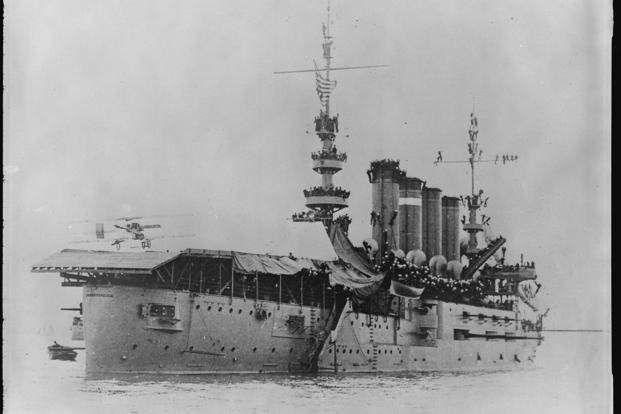

And Ely was not done making military aviation history, either. He later became the first pilot to land and take off from a warship when he departed from Tanforan Race Track in California, flew 13 miles and came to rest aboard the cruiser USS Pennsylvania in San Francisco Bay on Jan. 18, 1911. After lunch and some photo ops, Ely returned to the track. That flight also marked the first use of the tailhook system that has become commonplace in modern naval aviation.

Capt. C.F. Pond, the Pennsylvania's skipper, described the achievement as "the most important landing of a bird since the dove flew back to the ark," according to a 1981 story from the U.S. Naval Institute. Ely was suitably impressed as well, telling the San Francisco Examiner: "For the first time in my life, the feeling that I had actually done a great thing came over me."

While the Navy was not the first U.S. military branch to embrace fixed-wing aviation -- Lt. Benjamin Foulois piloted the Army's first aircraft over Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston in Texas on March 2, 1910, roughly eight months before Ely's takeoff from the USS Birmingham -- 1911 was a transformative year for the service in the air. For the first time, the Navy trained officers to become pilots, bought airplanes and established naval aircraft operation sites in Maryland and California.

Ely tragically died two days before his 25th birthday that year after crashing his plane during an exhibition in Macon, Georgia. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously in 1933, and his exploits are commemorated in an exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution's Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., which includes a certain damaged propeller.

-- Stephen Ruiz can be reached at stephen.ruiz@military.com.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.