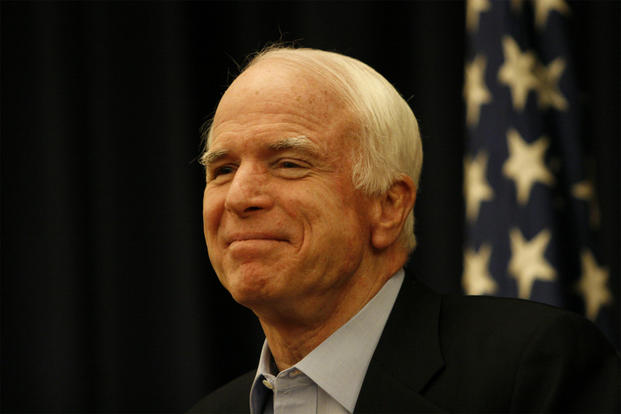

Editor's Note: Sen. John McCain died Aug. 25, 2018, two months after this story was first published. He was granted the rare honor of lying in state at the U.S. Capitol and was buried at the U.S. Naval Academy Cemetery in Annapolis, Maryland.

The lout of a prison guard they called the "Bug" told Bud Day with a satisfied smirk that, "We've got the Crown Prince."

As usual, Day, an Air Force major who would later receive the Medal of Honor, ignored the Bug.

Later in December 1967, the guards hauled a new prisoner strapped to a board into Day's cell.

Day was in bad shape himself. He had escaped and was on the run for two weeks before being caught. The beatings had been merciless, but the condition of the new guy was something else.

"I've seen some dead that looked at least as good," Day would later reportedly say. The new prisoner was in a semblance of a body cast. He weighed less than a hundred pounds. He had untended wounds from bayonets. His broken and withered right arm protruded from the cast at a crazy angle.

Day thought to himself that the North Vietnamese "have dumped this guy on us so they can blame us for killing him, because I didn't think he was going to live out the day."

Then Day caught the look: "His eyes, I'll never forget, were just burning bright," and "I started to get the feeling that if we could get a little grits into him and get him cleaned up and the infection didn't get him, he was probably going to make it."

"And that surprised me. That just flabbergasted me because I had given him up," Day said, as recounted in the book "The Nightingale's Song" by Marine Vietnam War veteran Robert Timberg.

Day had just met Navy Lt. Cmdr. John Sidney McCain III, or as Radio Hanoi called him, "Air Pirate McCain." Day realized this was the Bug's "Crown Prince," the son of Adm. John S. McCain, Jr., commander of U.S. Pacific Command.

Two Reckonings

The nearly five years he spent as a POW were a reckoning for the future senator from Arizona.

But now, he's facing a different kind of reckoning.

In July 2017, he was diagnosed with glioblastoma, a form of brain cancer that usually is terminal.

Shortly after the diagnosis, McCain went to the Senate floor to plead for bipartisanship.

"Stop listening to the bombastic loudmouths on the radio and on the Internet. To hell with them," he said.

"We've been spinning our wheels on too many important issues because we keep trying to find a way to win without help from across the aisle," he added. "We're getting nothing done, my friends; we're getting nothing done."

McCain, still chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, went home to Arizona before Christmas and has not returned.

Before leaving the Senate, McCain said in a floor speech that "I'm going home for a while to treat my illness," McCain said in a floor speech before leaving the Senate. "I have every intention of returning here and giving many of you pause to regret all the nice things you said about me."

"And I hope to impress on you again, that it is an honor to serve the American people in your company," McCain added.

At his ranch in Sedona, Arizona, McCain has reportedly not been a model patient. He has jokingly accused his nurses of being in the witness protection program.

"His nurses, some of them are new, they don't really know him, so they don't understand that sarcasm is his form of affection," Salter said Monday on the "CBS This Morning" program.

"He fights, he's fought with everybody at one point or another," Salter said. "You know, he always talks about the country being 325 million opinionated, vociferous souls -- and he's one of them."

In an audio excerpt from the book, McCain faced mortality.

"I don't know how much longer I'll be here," he said in the book. "Maybe I'll have another five years. Maybe with the advances in oncology, they'll find new treatments for my cancer that will extend my life. Maybe I'll be gone before you hear this. My predicament is, well, rather unpredictable."

Maverick No More

In the 1990s, A&E ran a documentary on McCain that included in its title the moniker "American Maverick." The title was probably suitable for a politician who clashed so frequently with others but managed to maintain friendships with rivals, including Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Hillary Clinton.

McCain said he's seeking to shed the "maverick" label, discussing the subject in an HBO documentary on his life that will air on Memorial Day.

"I'm a human being and I'm not a maverick," McCain said in a trailer for the documentary obtained by ABC.

"I've been tested on a number of occasions. I haven't always done the right thing," he said, "but you will never talk to anyone who's as fortunate as John McCain."

Throughout his life and public career, McCain has demonstrated humor in dire circumstances and the ability to absorb grave blows and continue on.

When he was told that the Hoa Lo prison, dubbed the "Hanoi Hilton" by the POWs, had actually been turned into a hotel, McCain said "I hope the room service is better."

He could also be self-deprecating.

"I did not enjoy the reputation of a serious pilot or an up-and-coming junior officer," McCain, with long-time collaborator Mark Salter, wrote in his book "Faith of My Fathers," describing life before his A-4 Skyhawk was shot down over Hanoi.

He had crashed three planes in training. He was assigned to attack aircraft and was not among the elite who flew fighters.

The look that riveted Bud Day in the prison camp signaled that the gadfly and carouser McCain was renewing a commitment "to serve a cause greater than oneself."

It is a message that he has delivered to Naval Academy graduates and to congressional colleagues, and he has admitted to often falling short of living up to his own mantra.

After his return from Vietnam, there was a failed marriage and his implication in the "Keating Five" scandal, a bribery affair with a a corrupt wheeler-dealer that almost ended his career in politics.

McCain recently described to CNN's Jake Tapper how he wanted to be remembered.

"He served his country, and not always right," McCain said. "Made a lot of mistakes. Made a lot of errors. But served his country. And I hope you could add 'honorably'."

On the Campaign Trail With McCain

The famously named "Straight Talk Express" campaign bus was actually reduced to a minivan when McCain was broke and running on fumes in the New Hampshire presidential primary of 2008. The few reporters still covering him had no problem squeezing in. The small group included this reporter, who covered the McCain campaigns for the New York Daily News in 2000 and 2008.

McCain would be off to some high school gym to speak, but mostly to listen. Everybody knew the script, because there wasn't one, and that's part of what made him a treat to cover.

His "Town Hall" events really were town halls. There might be a talking point at the top, or some message of the day fed to him by handlers, but McCain would get rid of it quickly and throw it open to the floor.

The practice had its downside. There was the guy who seemed to show up everywhere and always managed to grab the mic. He wanted to grow hemp, or maybe smoke it, and thought McCain should do something about it. It drove the candidate nuts.

The ad-lib nature of his campaigns sometimes backfired. There was the time in New Hampshire when he was headed to Boston for a Red Sox game and a sit-down with pitching hero Curt Schilling. Red Sox? New Hampshire primary? Impossible to screw that up.

The news of the day was that opponent Mitt Romney had hired undocumented immigrants to sweep out his stables, blow the leaves off his tennis courts, or similar tasks.

A small group of reporters hit McCain with the Romney question on his way to the car. McCain hadn't heard. He started to laugh, thought better of it, and rushed back inside the hotel.

He could be seen in the lobby doubling up as aides explained the Romney situation. He came back out, said something to the effect of, "Of course, if true, this is troubling ... " and went to the ballgame.

Somebody wrote that McCain was the only candidate who could make you cry, and that was true.

In 2000, McCain was basically beaten when the campaign reached California. George W. Bush would be the Republican nominee.

McCain was running out the string in San Diego with many of his old Navy buds. On the dais was Adm. James Stockdale, who had been the senior officer in the prison camps. Stockdale received the Medal of Honor for his resistance to his captors.

Somehow, Stockdale had become the running mate of the flighty and vindictive Ross Perot, who had disrespected him and sidelined him from the campaign.

In his remarks, McCain turned to Stockdale and said that, no matter what, "You will be my commander -- forever."

There was a pause, and then the crowd stood and applauded.

His friends from the prison camps would occasionally travel with him on the bus or the plane. They were easy to pick out. During down times, they were the ones who would rag on him about what a lousy pilot he had been. It was a learning experience for those who covered McCain.

One of the former POWs was Everett Alvarez, who was the longest-held Navy pilot from the camps. At an event in California, there was a great rock n' roll band that opened and closed for McCain. Outside the hall, as the crowd filed out, Alvarez was at an exit, enjoying the band as they blasted out '60s hits.

"Great stuff," he said to this reporter, who wondered later whether that was the first time Alvarez was hearing it.

Son Of A Son Of A Sailor

The title of the cover song of a Jimmy Buffett album applies to John McCain: "Son Of A Son Of A Sailor."

His grandfather, John S. "Slew" McCain Sr., was an admiral who served in World War I and World War II. His father, John S. McCain Jr., was an admiral who served in submarines in World War II. Both father and grandfather were in Tokyo Bay after the Japanese surrender in World War II.

John S. McCain III was born on August 29, 1936, at Coco Solo Naval Air Station in the Panama Canal Zone. The family moved 20 times before he was out of high school, and his transience became an issue when he first ran for Congress in 1982.

His opponent tried to pin the "carpetbagger" label on him, and said he had only recently moved to Arizona. McCain said his opponent was correct: the place he had been in residence longest was Hanoi. He won easily.

McCain was an indifferent student and his poor academic record continued at the U.S. Naval Academy, where he graduated in 1958 fifth from the bottom in a class of 899.

After flight school, he was assigned to A-1 Skyraider squadrons and served on board the aircraft carriers Intrepid and Enterprise.

In 1967, in his first combat tour, he was assigned to the carrier USS Forrestal, flying the A-4 Skyhawk in Operation Rolling Thunder.

On July 29, 1967, McCain was in his A-4 on the flight deck when a missile on a following plane cooked off and hit the A-4, starting a fire that killed 134 and took more than a day to bring under control.

McCain transferred to the carrier USS Oriskany. On Oct. 26, 1967, McCain was flying his 23rd combat mission over North Vietnam when his aircraft was hit by a missile. He broke both arms and a leg when he ejected and nearly drowned when his parachute came down in Truc Bach Lake in Hanoi.

McCain's decorations include the Silver Star, three Bronze Stars with combat 'V' devices, the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Purple Heart.

"In all candor, we thought our civilian commanders were complete idiots who didn't have the least notion of what it took to win the war," McCain would later write of the Vietnam war.

A Final Fight

McCain did not vote for President Donald Trump. The antipathy was there when Trump said during the campaign that McCain was "a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren't captured," but the break came later when a video emerged of Trump spewing vulgarities about women.

In speeches and in his writings since, McCain has not referred to Trump by name but made clear that he is opposed to some of the policies and crass appeals that won Trump the election.

In an address in October 2017 at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, McCain said that it was wrong to "fear the world we have organized and led for three quarters of a century, to abandon the ideals we have advanced around the globe, to refuse the obligations of international leadership, and our duty to remain the last, best hope of Earth."

He said it was wrong to abandon those principles "for the sake of some half-baked, spurious nationalism cooked up by people who would rather find scapegoats than solve problems."

To do so was "as unpatriotic as an attachment to any other tired dogma of the past that Americans consigned to the ash heap of history," McCain continued.

While hoping for recovery, McCain has made plans for what comes next. He said in the HBO Memorial Day documentary that "I know that this is a very serious disease. I greet every day with gratitude. I'm also very aware that none of us live forever."

In his new book, McCain said that he was "prepared for either contingency."

"I have some things I'd like to take care of first, some work that needs finishing, and some people I need to see," he said.

He has asked that Barack Obama and George W. Bush give eulogies when his time comes. He has asked that Trump not attend his funeral.

McCain has also asked that he be laid to rest alongside Adm. Chuck Larson at the Naval Academy's cemetery in Annapolis. Larson, who was twice superintendent of the Naval Academy, was McCain's roommate at Annapolis.

In a message of his own on Memorial Day 2017, McCain recalled his friend, the late Air Force Col. Leo Thorsness, a Medal of Honor recipient for his valor in Vietnam. Thorsness was shot down two weeks after the actions for which he would receive the medal.

"I was in prison with him, I lived with him for a period of time in the Hanoi Hilton," McCain said.

Through the nation's history, "we've always asked a few to protect the many," McCain said. "We can remember them and cherish them, for, I believe, it's only in America that we do such things to such a degree."

-- Richard Sisk can be reached at Richard.Sisk@Military.com.