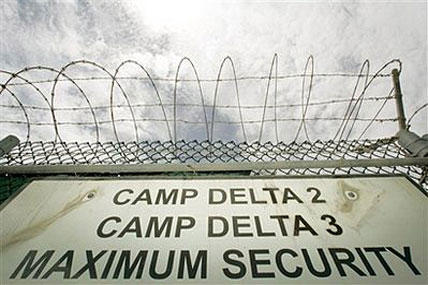

President Obama on Tuesday renewed his long-dormant commitment to closing the Guantanamo Bay prison, which would require the cooperation of a gridlocked Congress that has already passed laws barring the move.

“It needs to be closed. I’m going to go back at this,” Obama said as the Navy sent more corpsmen, nurses and detention specialists to Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba to cope with a hunger strike by more than half the inmates.

House leaders quickly signaled they would seek to scuttle any proposal by the president to shut down the detention facility and move selected prisoners to the U.S. for trials in federal courts.

“The president faces bipartisan opposition to closing Guantanamo Bay's detention center because he has offered no alternative plan regarding the detainees there, nor a plan for future terrorist captures,” Rep. Howard P. “Buck" McKeon (R-Calif.), chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, said in a statement.

At a White House news conference marking the first 100 days of his second term, Obama acknowledged that “it's a hard case to make” for closing the prison “because for a lot of Americans, the notion is out of sight, out of mind, and it's easy to demagogue the issue."

"I understand that in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, with the traumas that had taken place, why for a lot of Americans the notion that somehow we had to create a special facility like Guantanamo and we couldn’t handle this in a normal, conventional fashion -- I understand that reaction. But we’re now over a decade out. We should be wiser. We should have more experience in how we prosecute terrorists," Obama said.

Closing Guantanamo was part of Obama’s platform in his first run for the presidency but went largely without mention in his bid for a second term.

His attempt to move the trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the self-proclaimed mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, to federal court in Manhattan fell apart against local opposition and prompted Congress to pass a law barring the use of Defense Department funds for the transfer of Guantanamo prisoners.

However, Obama said that Guantanamo was a stain on national honor that required action.

"The notion that we're going to continue to keep over 100 individuals in a no-man's land in perpetuity -- even at a time when we've wound down the war in Iraq, we're winding down the war in Afghanistan, we're having success defeating al-Qaida, we've kept the pressure up on all these transnational terrorist networks, when we've transferred detention authority in Afghanistan -- the idea that we would still maintain, forever, a group of individuals who have not been tried, that's contrary to who we are, it's contrary to our interests, and it needs to stop," Obama said.

Currently, Guantanamo houses 166 inmates, and the military’s Joint Task Force Guantanamo has estimated that 100 were participating in a hunger strike, with 21 of the 100 approved to be force-fed the nutritional supplement “Ensure” through a tube inserted through the nose into the stomach.

Lawyers for the detainees and human rights activists have charged that the hunger strike was triggered by their despair at ever being put on trial or released.

At least 86 of the 166 inmates have been “cleared for release,” according to their lawyers, but a Defense Department spokesman, Lt. Col. Todd Bresseale, said “there’s no such thing as ‘cleared for release.’ ”

Bresseale said that “56 are slated for potential transfer” to their home countries or to another country willing to take them, and 30 others have been authorized for “conditional release,” which he likened to parole.

Last week, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., head of the Senate Intelligence Committee, wrote to the White House declaring that the status of the prisoners needed to be reconsidered.

"The fact that so many detainees have now been held at Guantanamo for over a decade and their belief that there is still no end in sight for them is a reason there is a growing problem of more and more detainees on a hunger strike," Feinstein wrote.