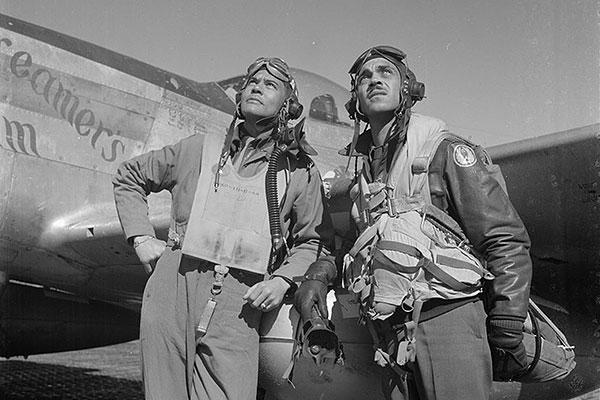

Despite what the movie "Top Gun" suggests, the U.S. military's first real-world "Top Gun" program wasn't set up by the Navy. It was an Air Force program that first took place in 1949. Tuskegee Airmen Capt. Alva Temple, 1st Lt. Harry Stewart, 1st Lt. James H. Harvey III and alternate Halbert Alexander, competing in P-47N Thunderbolts, would win it.

Though the Tuskegee Airmen are to military aviation what Jackie Robinson is to major league baseball, many Americans still have not heard of them.

Prior to World War II, many in the military believed that African-Americans would not perform well in combat and were incapable of flying. A 1925 study conducted by the Army War College concluded that African-Americans were inherently ill-suited for combat physically and psychologically.

In 1939, the government began establishing flight schools at colleges around the nation but refused to do so at any of the Black colleges. A Howard University student lodged a lawsuit in protest, and thanks to mounting pressure from black newspapers, the NAACP, and sympathetic government leaders, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor, the "Tuskegee Experiment" was begun. A flight school was founded at the historic Tuskegee University in Alabama, and On July 19, 1941, the Army Air Corps initiated the program.

At its inception, twelve cadets and one officer, Captain Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., who later became the Air Force's first African American general, were in the program. These and later graduates became known as "Tuskegee Airmen," and formed the 99th Pursuit Squadron. The 99th fought with distinction in the Mediterranean Theater, and later joined three newer Tuskegee squadrons to form the 332nd Fighter Group. The 332nd distinguished itself in Italy, flying combat missions and escorting bombers.

The "Tuskegee Experiment" was expected to fail. However, not only was the program a milestone in training African-Americans as military pilots, but the Tuskegee Airmen went on to succeed with flying colors. Tuskegee pilots garnered some of the most envied military records in history, and more importantly advanced the American Civil Rights Movement by setting the precedent that would force the American military to begin to fully integrate in 1948 — more than a decade before Martin Luther King Jr. marched on Washington.

The Tuskegee program also forged a group of men who would earn advanced degrees and make notable achievements in the fields of law, social policy, politics, medicine, education, and finance. Surprisingly, aviation was not on this list, as private aviation industries were closed at the time to African-Americans.

That the 926 servicemembers who graduated from Tuskegee succeeded at a time when racist attitudes were officially sanctioned in the military is a testament to the men's extraordinary determination to succeed as pilots, which by its nature is one of the most academically and psychologically challenging areas of military service.

Related video:

The Program at Tuskegee

"Hands down, Tuskegee was much harder," says Harold Hoskins, shaking his head.

As a former student both at Tuskegee and later at an integrated pilot school at Texas' Randolph Air Force Base, and having served under Colonel Benjamin Davis and logged 9500 flight hours in the Air Force, Hoskins is in a unique position to compare both experiences. Since retiring from the Air Force, he has become Assistant V.P. of Student Affairs at California State University in Hayward.

"The Tuskegee program was so rigorous, you didn't have time to think," says Hoskins. "A history master's student, who happened to be Jewish, was interviewing me for her thesis, asked me if I knew anything about the Holocaust. Honestly, all that was on my mind was 'Can I get through this program?' I didn't have the faintest idea about the Holocaust, nor about anything else that was happening in American society either, for that matter."

An initial part of the Tuskegee experience was getting hazed by upper classmen, a tradition brought over from the military academies and four national Black fraternities where many cadets had gone to school before enlisting in the Army Air Corps. Cadets were forced to "eat a square meal": they were only allowed to sit on one corner of their dining room chair, made to sit perfectly straight, and bring their forks from their plates to their mouths at a perfect right angle, without moving their heads. If food was dribbled, the cadet had to stand up and scream the humiliating phrase, "I am a sloppy dummy."

Pre-flight cadets were also awoken in the middle of the night, ordered to put on their rubberized ponchos and gas masks, and made to do various physical drills all night — while still being expected to do their full physical training regimen in the morning, which began at 6 a.m., as well as class all afternoon.

"I guess it was supposed to make you tougher," explains Hoskins. "But when I got to Texas, I found out those white boys had no idea what hazing and fazing was all about. I didn't let on, but Texas was a piece of cake.

"Just to give you an example, we had to hem our own pants and sew on our own buttons on our shirts at Tuskegee. At Texas, we had tailors!" he laughs. "At Texas, they even customized our shirts so they fit just right and we looked sharp. At Tuskegee, we had to make sharp folds in our shirts, wrapping them sometimes all the way to our backside, to make them fit properly."

It is important to note that at the time African-American pilots trained at Tuskegee, the military was still completely segregated, which means the pilots' planes serviced by African-American mechanics and other specialists. Armament specialists trained at Lowry Field in Colorado, radio specialists at Scott Field, Illinois, and mechanics at Chanute Army Air Field in Illinois.

Combat Operations

In addition to fighting for their country, the Tuskegee pilots knew that the future of African-American pilots in the military rested on their performance, quite a heavy burden for 18-year-olds. Though many commanding officers did not want to employ Tuskegee fighters, Colonel Davis, a brilliant military strategist and lifelong military man, fought successfully for their chance to display their skills. The rest is history.

During the course of the war, 66 Tuskegee pilots were killed in combat, and 32 pilots were shot down and became prisoners of war. The Tuskegee pilots shot down 409 German aircraft, destroyed 950 units of ground transportation and sank a destroyer with machine guns alone — a unique accomplishment. However, their most distinctive achievement was that not one friendly bomber was lost to enemy aircraft during 2000 escort missions. No other fighter group with nearly as many missions can make the same claim. Reflecting their superior performance, they were called "Black Birdmen" by the Germans, and given the nickname of "Black Redtail Angels" by the Americans (because of the vivid red markings on their aircraft tails).

It was Davis' idea to require that fighter pilots escort bomber planes, and to absolutely under no circumstances abandon the bomber pilots. Because of the Tuskegee Airmen's success, Davis' policy became National Air Corps policy.

"That's why there was never an 'ace' Tuskegee pilot," says Attorney James Goodwin, 1st Lieutenant from class 44H, who went on in civilian life to become one of the architects for Affirmative Action admission policies for the University of California system. "Because of Benjamin Davis' orders to the fighter pilots ... Tuskegee pilots never lost a bomber. It's a military record that is enviable."

An "ace" was a pilot who shot down five or more enemy planes. But with fighter pilots getting downed in battle 60 to 70 percent of the time, being an "ace" was dangerous business — and the reason so much glory is attached to the title. However, Davis encouraged his fighter pilots to start thinking for the good of the whole squadron, rather than for individual records.

The Freeman Field Incident

With all their successes in the field, Tuskegee officers found that when they returned from Europe, they were still second-class citizens at home. Their contributions to American freedom had not endeared them to some of their white military brothers, and some feared lynching by mobs if they dared to leave the base.

Although there is much more to the story of the societal obstacles the African-American officers had to overcome, tensions culminated in an outright protest in spring 1945 at Freeman Field in Indiana. In March 1945, the last of the Tuskegee groups, the 477th Medium Bombardment Group, was moved from Godman Field, adjacent to Fort Knox, to Freeman Field because of the latter's better flight facilities. Tensions between the 477th and the white command structure on the base were tense as soon as the 477th arrived, and shortly thereafter, as Robert Rose declares in Lonely Eagles, "an incident occurred unparalleled in Air Corps history."

Upon their arrival at Freeman, the commanding officer of the base, Colonel Robert R. Selway, moved quickly to set up and enforce a segregated system. The group was housed in a dilapidated building. Col. Selway also created a novel system to deny the Airmen entry into the officers' club. He classified the Black airmen as "trainees," even though they had all finished flight school, and therefore were all commissioned officers. As trainees, they were forced to use a run-down, former noncommissioned officers club nicknamed "Uncle Tom's Cabin." This all occurred despite an order issued in 1940 issued by President Roosevelt himself that no officer should be denied access to any officer's club.

On April 5, 1945 a group of the Airmen peacefully entered the officers' club in protest. Sixty-one were arrested within 24 hours. One Airman, Roger Terry, was convicted by a general court martial for assault — for brushing against a superior officer while trying to enter the club. Later, the officers were asked to sign a statement saying that they understood and agreed with the policy of segregated clubs on base. One hundred and one refused to sign, and received reprimands for the action. Despite being given direct orders not to enter the club again, officers later tried to reenter the officer's club. During a time of war, disobeying a direct order can be punishable by death.

"These officers had no idea what was going to happen to them when they did that," says Leslie Edwards, a flight chief who had one of the safest mechanic's records during World War II, and witnessed the Freeman Incident, recalls. "They had no idea if they were going to be shot — really. But they just knew that they couldn't take it anymore. If they were about to be sent off to the Pacific to possibly die there, they might as well die right there. I saw these men cry when they had to choose to sign the statement [that they would follow the racist orders] or not. It was a brave, brave thing those men did.

"Not every white person wanted the African-American officers out of the O Club," continues Edwards. "It's only human to want to have fellowship and friendship and want to enjoy the company of one another, and share their experiences. It's a shame that it was the leadership that wanted to separate everyone. I think many of them hated the separation as much as we did. It was just the [leadership] who wanted to force everyone to be separated."

Colonel Selway was later fired as Commander of the 477th because of his policies, and Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. assumed command. At the 24th annual convention of Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. in 1995, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force Rodney Coleman announced that the Air Force would exonerate all of the officers involved in the incident.

Inspiring Heroes

Tuskegee pilot John H. Leahr, who logged 329 hours of combat flying time and after his illustrious military career went on to be one of America's first African-American stockbrokers, has one important lesson to pass on: "Don't let anyone tell you that you can't do something. If you're determined enough, you can overcome anything." Leahr says that if this adage is true for him, it can be true for anyone.

"I never passed an Army physical," laughs the 81-year-old, referring to his right leg, which was permanently injured at age 7. "But I guess I talked my way through it. They [the army health officials] were going to make me a "4F" [a grade that means "unfit for service"] but I told them to go ahead and make me a "1A" because I was gonna fly airplanes. They shook their heads and said there was no way I could mechanically operate the rudder pedals.

"I told them, 'If you make me a 1A, I'll handle the rest.' So I got through that part, and six months goes by, and it was time for another physical. Again, I couldn't do the running part. I convinced the officials to pass me, explaining that if I was good enough for the army health inspectors who, when they gave me their 1A rating expected me to be strong enough to march across America, surely I was healthy enough to be inside an airplane.

"It worked. The next time the physical came due, I just pointed to the fact that I had passed the last physical. After the second time, they didn't bother giving me physicals any more. I went on to fly 132 combat missions. So never let anyone tell you that you can't do something."

Indeed, the first African-American 4-star general was also a Tuskegee-trained pilot. Gen. Daniel "Chappie" James flew in the 477th Bombardment Group during WWII, because his 5'11" frame was too tall to fly fighter planes. Chappie finally got the opportunity to fly fighter missions in Vietnam, after the military introduced jets with larger cockpits.

Tuskegee Airmen, Inc.

One of over 45 official chapters nationwide, the San Francisco Bay Area chapter of Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. continues the struggle for equality the Airmen began fifty years ago. Though most of the Airmen are in their seventies and eighties, their fire and commitment to serve the community has not dimmed.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon in Oakland, California, members of the chapter show up for their monthly meeting. They greet each other like old friends, tell stories, joke, and good-naturedly argue about their famed unit's history. One member brings an out-of-print yearbook and they reminisce over old photos. They also pass around a Tuskegee Airman GI Joe figure for each member to sign.

But the festive atmosphere belies the more serious work they engage in. Like every chapter, they do charitable activities year-round: speaking at schools, attending events like the Monterey Jazz Festival, and volunteering any way they can — to show the youth "a better way of doing things," says Chapter president Sam Broadnax.

Their most ambitious project is the Summer Flight Academy. Every year, the Airmen offer free flying lessons to at-risk teenagers. Presently in its seventh year, the summer program only accepts students from the most troubled backgrounds. They provide both ground school and flight training, and even take care of lunch. The kids and their families pay nothing, Broadnax notes proudly.

Nearly a hundred kids have gone through the training. Only one has been dismissed and none has dropped out — close to the perfect record the Airmen had escorting bombers in World War II. Broadnax points to one student who was in a youth detention center, and was let out to attend class. In jail for being part of a hold-up gang, he became class valedictorian and is now gainfully employed. Broadnax says the summer flight school "does something magical."

Unfortunately, funding has dropped off and Broadnax notes that they have had to "beat the bushes" to find other sources. They are looking forward to new charitable efforts, including scholarships for local students, but the biggest challenge is finding money. If history is any indication, they will not give up this battle without a fight.

Tuskegee Airmen Resources

The 1995 HBO-produced movie The Tuskegee Airmen, starring Laurence Fishburne and Cuba Gooding Jr., is considered by Tuskegee veterans to be a decent primer if you know nothing about the Tuskegee story, and is credited with helping revive interest in their exploits. The movie does have its inaccuracies, as will happen with any fictitious account of a real-life story ("That was a movie, not a documentary," quips San Francisco Bay Area Tuskegee chapter president Sam Broadnax).

For example, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt is shown getting into an open cockpit to take a spin with an African-American pilot (who is unnamed in the movie, but in reality was Alfred C. Anderson — affectionately known as "Chief" — and is most famously known as the architect of "primary training," the first phase of pilot training at Tuskegee). However, any Tuskegee veteran can tell you there is no way Mrs. Roosevelt could have flown in an open cockpit plane gracefully, wearing a skirt.

The film opens with a shot of a young boy sitting in a open field playing with a model airplane that he built himself, dreaming that one day he will become a pilot. Many veterans will tell you, "That was me." Since the scene captures, in essence, their own childhoods, they forgive the minor transgressions made in the name of "Hollywood," even the scene that depicts one Tuskegeen committing suicide. "That never happened either," says Hoskins, shaking his head.

Another criticism of the HBO movie (in fact, one of the major criticisms of all popular literature about the Tuskegee experience) is that the focus is always on the fighter pilots. However, 40 percent of the pilots trained at Tuskegee went on to become bomber pilots. "All the glory went to the fighter pilots," says Broadnax, who himself was also a former fighter pilot that graduated with class 45A. "But for every pilot in the air, there were ten specialists on the ground who supported that one pilot. It's a shame they never get any credit or attention."

Until now, the bomber pilots, bombardiers, navigators, gunners, radio specialists and ground engineers whose mission it was to keep the planes in optimum fighting condition have been unsung heroes. Broadnax hopes to complete a novel this year to fill this void, and finally give the voices of all these other Tuskegee professionals a place to be heard.

For those looking to hear stories of Tuskegee pilots first-hand, there are several options. The Tuskegee Airmen National Museum, located at historic Fort Wayne in Detroit, Mich., has an impressive collection of memorabilia and models of all the planes flown by Tuskegee pilots. For details about admission prices and operations hours, contact the museum at (313) 843-8849.

In addition, 45 chapters of Tuskegee Airmen around the nation boast membership of many surviving Tuskegee crew, pilots and teachers. These chapters are available to arrange speakers and give presentations. For more information, check out the National Headquarters for the Tuskegee Airmen to find a chapter near you as well as hear about coming events in your local area.

Getting to rub elbows with living history is one of the main reasons airplane mechanic Willie J. Norton joined the Cincinnati chapter of Tuskegee vets, and now he serves as chapter president. "They are ambassadors, role models, mentors," says Norton. "It's an honor to hear their stories, many of which they don't share with the general public, but they will once they get to know you, and if you ask."

The Tuskegee Planes

The all-black 332 Fighter Group flew more different kinds of fighter planes than any other group during WWII. While not so challenging for the pilots, who say that once you know how to fly one plane, you can pretty much fly them all, it placed extreme pressure on the mechanics who had to service these planes.

"The mechanics really did a yeoman's job of keeping our planes in tip-top shape," says Sam Broadnax. "It was extremely difficult to learn the schematics of completely different engines, and be able to jump from one type of engine to the other."

Tuskegee mechanics had some of the best mechanical records of WWII. The mechanics often worked round-the-clock, sleeping in shifts in the airplane hangers where they were working. The mess hall would bring food out to them, so they would not be delayed a single second from finishing their work on the planes.

Some of the planes the Airmen used include:

- P-39 (engine behind pilot)

- P-40 (inline engine)

- P-47 (air-cooled radial engine in front of pilot)

- B-25 (twin-engine bomber)

- P-51 (the famous Tuskegee "Red Tails")

- P-51 at Redtail.org (more information and pictures)

Related links

- The Tuskegee Airmen - 332nd Fighter Group - Features a list of combat statistics, and includes an amusing story of Eleanor Roosevelt's ride with one of the pilots.

- Tuskegee Airmen Inc. - National organization provides info on its events, as well as an historical examination of the Tuskegee pilots.

- Tuskegee Airmen Fact Sheet - The Air Force's fact sheet on the Tuskegee Airmen