In February 1945, the United States assembled a force of paratroopers, glider troops, and Filipino and Chinese resistance fighters in a highly detailed, coordinated attack on a Japanese prison complex in the Philippines. More than 2,000 military and civilian prisoners had been held at the Los Baños prison camp since Japan captured the islands in 1942.

To get them out, the Americans would need to achieve total surprise against 250 Japanese guards, lest they arouse 10,000 enemy reinforcements. To succeed would mean the rescue of thousands of starving Allied prisoners. If they failed, the Japanese would certainly kill every last one of them.

The result was one of the most perfectly executed rescue missions in modern history.

Japan began its attack on the Philippines at the same time it struck Pearl Harbor, but did not fully occupy the islands until the middle of 1942. Once in control, the Imperial Japanese Army not only imprisoned American and Filipino troops, it also interred thousands of American and sympathetic civilians. When the U.S. Army finally returned to the Philippines in 1944, it was essentially coming back to a hostage situation.

The island of Luzon alone had four major prison camps; two in Manila, one in Cabanatuan and the fourth at Los Baños. By the end of February 1945, Cabanatuan's 552 Allied prisoners of war would be rescued, along with the 800 in Manila's Bilibid Prison. Another 500 civilians were imprisoned at Bilibid, and 4,000 more civilians were held at Santo Tomas University in the capital.

All that was left on Luzon was the prison at Los Baños, and Gen. Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of allied forces in the Southwest Pacific, wanted the thousands of civilians there liberated before the Japanese could kill them as a reprisal.

The Los Baños prison was situated deep in enemy territory some 40 miles from the front, between the north shore of Laguna de Bay and the foothills of Mount Makiling to the south. To the southeast was the Japanese 8th Division, 9,000 to 11,000 enemy troops who could respond to any attack by rail or by road. Time was of the essence, but given its position, liberating the prison camp could have taken weeks. Based on reports from the other liberation missions, the U.S. believed the 2,147 civilian and military prisoners at Los Baños might have been killed, starved or left for dead by then.

With the latest intelligence on enemy positions and routines from Los Baños escapees, Army planners created a four-phase assault that was meticulously timed to keep the guards' reactions minimal and move thousands of civilians. Failure anywhere meant failure everywhere, according to Lt. John Ringler, who led the air assault.

The first phase was inserting a recon platoon from the 11th Airborne with Filipino guerrillas using local fishing boats. Next, Company B, 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment and a machine gun platoon from the battalion's headquarters company would parachute into the area. While they were landing, Filipino guerrillas from the 45th Hunters ROTC Regiment would attack the camp.

After eliminating the enemy, LVT-4 Amtracs would ferry the rest of the 1st Battalion across Laguna de Bay and transport the prisoners away from the prison. The final phase required the 11th Airborne's 188th Glider Infantry Regiment to make a diversionary attack on the Japanese 8th Division to prevent it from responding to the prison raid.

For this four-phase plan to work, all four steps would have to begin simultaneously -- no small feat for an operation that required the coordination of thousands of people. It would also require an estimated five hours to move all the people, which meant 170 U.S. paratroopers and 75 Filipino guerrillas would need to hold the camp and protect the prisoners for that time.

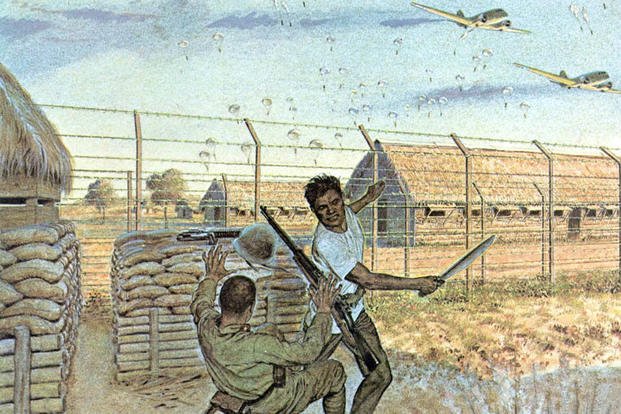

At 7 a.m. on Feb. 23, 1945, as the Japanese guards performed calisthenics in only their loincloths, the sky above Los Baños filled with white parachutes. Then, the shooting started. Camp guards who managed to escape from the grounds were caught by the Hunters ROTC guerrillas waiting in the jungles with bolo knives and machetes. The combined force made short work of the surprised Japanese.

Not only did the coordinated assault happen with perfect timing, the LVT-4s landed on the beachhead at 6:58 local time. They came crashing through the prison's front gate and began moving the prisoners across the lake, on time and as planned. The Amtracs would have to make two trips to move everyone, which required time and patience. The rescue force at Los Baños could hear the cacophony of combat in the distance, which was the diversionary attack force from the 188th Glider Infantry Regiment cutting the Japanese 8th Division off from the prison raid.

The entire plan went off without a hitch, and the last of the LVTs departed the beach at 3 p.m., albeit under fire from the Japanese, who had finally begun to move toward the prison complex. In all, five Allied troops were killed and another six were wounded. Japanese losses were estimated at around 80. All 2,147 internees were rescued after three years of captivity. Among them was Frank Buckles, who would later be known as the last surviving American veteran of World War I.

Some 50 years after the Los Baños Raid, Gen. Colin Powell sent a letter to the 11th Airborne Division Association, a veterans group that included members of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, calling the raid "the textbook airborne operation for all ages and all armies."

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.