SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y. -- In 1918, there were two major killers in the world.

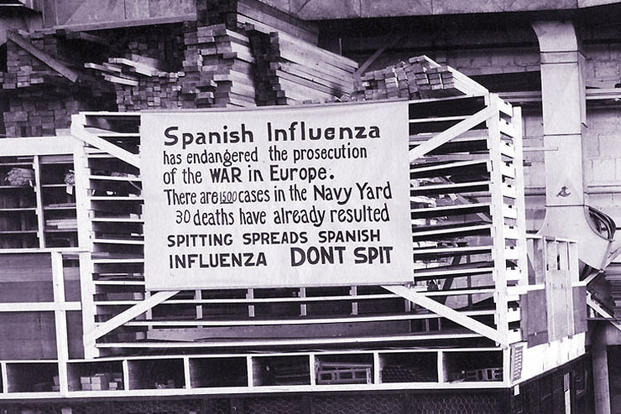

World War I, which would claim 20 million lives by its end, and the Spanish flu epidemic is estimated to have killed between at least 50 million people.

The flu struck an estimated 500 million people, some 28% of the world population.

American combat deaths in World War I totaled 53,402. But about 45,000 American soldiers died of influenza and related pneumonia by the end of 1918.

More than 675,000 Americans died of influenza in 1918. Based on today’s population, that would be the equivalent of 2.16 million Americans dying.

The disease that launched the worldwide pandemic was known at the time as the Spanish influenza.

Because Spain was not at war, newspapers there openly reported the virulent influenza. In the warring nations of Europe, information about the flu was kept out of newspapers so it did not hurt morale.

But many medical historians say it’s likely the virus launched itself onto the world from Haskell County, Kansas, and the United States Army helped move it along to become a worldwide killer.

In January and February 1918, according to the 2005 book “The Great Influenza,” local Dr. Loring Miner found people in the sparsely populated county -- 1,720 people occupying 578 square miles -- were coming down with a particularly violent strain of flu. Strong, healthy people died.

Miner was so concerned that in March 1918, he let the U.S. Public Health Service know what he had seen and warned of a new type of flu.

The disease burned itself out in March. In the past, it might well have never gotten beyond Haskell County. But in 1918, America was at war, and people were moving around the country more than ever.

Young men from Haskell County were training nearby at Camp Funston, what is now Fort Riley, Kansas. They reported to the camp for duty and went back and forth from home when on leave.

The local paper reported numbers of local boys on leave from Camp Funston while Miner was trying to figure out what was killing Haskell County residents in that fateful spring of 1918.

On March 4, 1918, the first influenza cases were identified at Camp Funston. Within three weeks, 1,100 of the 56,222 troops at the camp were sick. And because men were constantly moving among the Army’s camps all across the country, the virus spread.

On March 18, Camps Forrest and Greenleaf in Georgia reported influenza cases. By the end of April, 24 of the Army’s 36 main camps were reporting influenza outbreaks.

In April 1918, influenza hit Brest, France, one of the major debarkation ports for American soldiers who carried the flu with them to Europe.

Influenza was also reported among the civilian populations near Army camps. Civilians coming and going from the military camps, either visiting or doing business, were infected and brought the disease home with them.

During the spring of 1918, more than 11% of the 1.2 million soldiers in the United States were hospitalized with flu, although the death rate was not unusual.

The disease also jumped behind enemy lines.

German Gen. Erich Ludendorff, who had just led Germany’s last-ditch Kaiser Offensive to defeat the allies before the U.S. Army entered the war in force, remembered despairing because so many troops were sick and not on the front lines, he wrote in a book after the war.

With the arrival of summer, the virus disappeared. But in the fall of 1918, it had mutated and came roaring back.

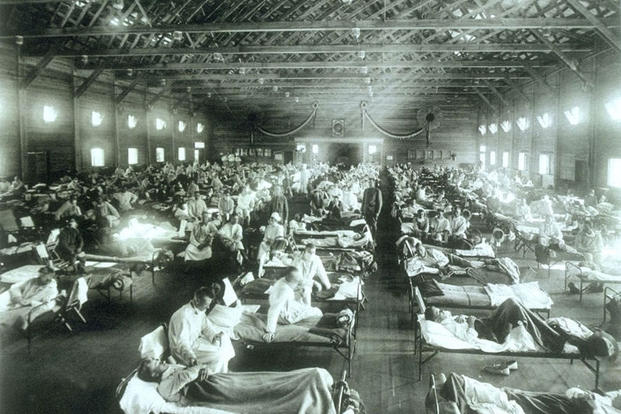

At Camp Devens in Massachusetts, the influenza virus appeared in September. By the end of the month, 14,000 soldiers at the camp were sick, a quarter of its population. A total of 757 of those men died.

The Army quarantined the camp, but before that happened, a contingent of troops was sent to Camp Upton on Long Island, just outside Yaphank. Camp Upton was where the National Guard’s 42nd Division had assembled and where the 77th Division -- composed of draftees from New York City -- had trained. The disease appeared at Camp Upton on Sept. 13.

Four days after the virus sent men to Camp Upton’s hospital, 171 of the 43,000 soldiers were sick. Col. John S. Mallory shut down the camp to civilian visitors and ended leaves for soldiers.

The action, Mallory told The New York Times, was to avoid the spread of the disease. He emphasized that there had been no deaths, and Camp Upton had not been hit as bad as other camps.

But by the end of September 1918, there were 3,050 influenza cases at Camp Upton and 401 soldiers suffering from pneumonia as well. Fifteen soldiers died on Oct. 1, 1918, increasing the total death number to 87.

The virus outbreak at Camp Upton reached its peak on Oct. 4, 1918, when 483 soldiers entered the hospital, according to a report compiled by the base hospital commander. On Oct. 5, there were 4,371 cases of influenza at the camp, 20 men had died that day, and soldiers were instructed to wear gauze masks to prevent infection, according to The New York Times.

“Soldiers will not be permitted to sit opposite each other at mess tables. Foodstuffs other than in sealed packages will not be sold in the post exchanges, and no person unmasked will be permitted in any YMCA or other welfare building,” the Times reported.

The post hospital was overwhelmed, so medical officers established temporary hospitals. Sheets were hung between beds to prevent further infection. Medical officers expressed horror at the sight of “the hopelessly sick and dying and at the magnitude of the catastrophe,” the Journal of the American Medical Society reported.

Naomi Barnett from Brockton, Massachusetts, traveled to Camp Upton to help care for her fiancé, Jacob Julian, when he fell ill with influenza. She planned to marry her soldier before he shipped off.

She died two days after arriving at Camp Upton. Jacob Julian died 30 minutes after her. The Camp Upton surgeon directed soldiers to stay in their own area of the camp unless they were on urgent business. Companies were locked down in their barracks if one case of flu was reported.

The measure, the surgeon reported afterward, worked when orders were followed. The camp’s remount station -- the troops responsible for providing horses -- followed strict quarantine procedures, and no men developed the flu, he reported. But the 3rd Development Battalion allowed officers and men to mingle throughout the camp, and “influenza was soon raging there.”

By the time the epidemic was considered over at Camp Upton -- on Oct. 22, when only 11 new cases were admitted -- 6,131 soldiers had been hospitalized, and 404 had died. New York’s other big Army camp in 1918 was just outside of Syracuse on the grounds of the New York State Fair.

Camp Syracuse was run by the 22nd Infantry Regiment. The regiment was responsible for training 10,000 to 12,000 recruits, most of whom were draftee soldiers from New England. A total of 14,000 soldiers and civilians lived and worked at what was formally known as the Syracuse Recruit Camp.

Influenza appeared at Camp Syracuse in September. There had been some isolated cases in August, but the numbers began going up on Sept. 12 after 10,000 recruits from Massachusetts had shown up on Sept. 4, according to a report from the camp surgeon. Because the camp was not a permanent facility, soldiers lived in overcrowded tents.

The camp had no hospital, so ill soldiers were sent to civilian hospitals in Syracuse or to Fort Ontario, a permanent Army post 35 miles away in Oswego, N.Y.

The camp had only three ambulances, one borrowed from Fort Ontario and two from Camp Dix in New Jersey. Eventually, the Yates Hotel in Syracuse loaned the camp a bus, which was used to move patients. Temporary hospitals were created in 12 existing buildings until 400 patients were housed.

There were 42 medical officers at Camp Syracuse (including two dentists), but a third of those officers were sick themselves just after the virus appeared. At Camp Syracuse, the total number of flu cases reached 2,289 out of an average strength of 12,000 people during the epidemic, which ended officially on Oct. 15. A total of 208 of the sick soldiers died.

Unfortunately, the need to send soldiers to local hospitals resulted in spreading the illness to Syracuse itself. By Oct. 4, 8,000 Syracuse residents were sick, and the Syracuse Herald was running a daily list of “plague victims.” By the time the epidemic ended, 900 Syracuse residents had died.

Influenza jumped outside the camps and went raging through the civilian population. Because of the way the virus worked, it was particularly frightening because it killed young men and women. Normally the flu killed the old and the very young. In 1918, the flu was killing young, able-bodied soldiers.

One of those soldiers was Pvt. James Down, who entered the Camp Upton hospital on Long Island on Sept. 23 and died Sept 26. An Army pathologist clipped a piece of Down’s lung, preserved it in wax and sent it to the Army Medical Museum.

In 1999, that section of Down’s lung helped doctors at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology determine what made the 1918 virus so deadly. Researchers in 2007 theorized that the 1918 flu forced a victim’s overstimulated immune system to kill the patient as it tried to fight off the virus.

In Europe, doctors of the American Expeditionary Force hospitalized 340,000 soldiers for influenza during 1918 while 227,000 soldiers were in the hospital due to wounds suffered in battle. In October 1918, as the American Army was locked in battle with the Germans in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, 1,451 Americans died from the flu. More 3rd Infantry Division soldiers were evacuated from the front with influenza than because of wounds suffered in combat.

German Gen. Ludendorff noted on Oct. 17 that the fighting power of the allied forces “has not been up to its previous level. … The Americans are suffering severely from influenza.”

The sickness and death at Army training camps even shut down the machinery of drafting men and making new soldiers. The Army stopped the intake of new draftees in October until the epidemic ended. Army Surgeon General Charles Richard also recommended against shipping more soldiers to France until the flu epidemic stopped, but President Woodrow Wilson decided against it.

The American Expeditionary Force was on the attack in France. The Germans were retreating. But men were being killed and wounded, and Gen. John J. Pershing, the commander of the AEF, demanded reinforcements.

Stopping the reinforcement convoys would give the Germans breathing room, Army Chief of Staff Peyton March argued, so they had to go on. Wilson agreed.

So troopships were loaded with soldiers who were well when they boarded but fell sick during the 10- to 14 day journey to Europe.

On board the S.S. Wilhelmina, a sailor watched as bodies were buried at sea from the S.S. Grant running next to his ship. He’d counted 15 such burials on one day during a voyage from New York City to France.

“I confess I was near to tears, and that there was tightening around my throat. It was death, death in one of its worst forms, to be consigned nameless to the sea,” he said.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.