SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y. — The casualty list released by the American Expeditionary Force on July 21, 1918, listed 64 American soldiers and Marines killed in action and 28 missing.

But the name reporters noticed first was that of a 20 year-old college student from Oyster Bay, Long Island: Lt. Quentin Roosevelt.

Quentin Roosevelt had been a public figure since he was 4 years old, when his father, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, became president.

Roosevelt had been missing since July 14, 1918, when he and four other pilots from the U.S. Army Air Service’s 95th Aero Squadron engaged at least seven German aircraft near the village of Chamery, France.

His father had been notified that he was missing and presumed dead on July 17 and took it hard.

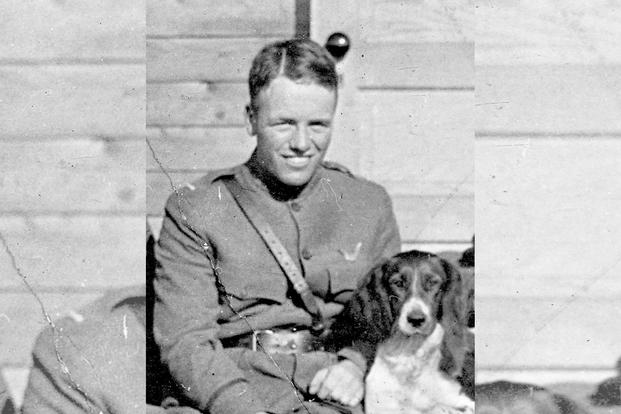

Quentin Roosevelt was a flight leader in the 95th, and despite his famous family, he was very much a regular guy.

“Everyone who met him for the first time expected him to have the airs and superciliousness of a spoiled boy,” wrote Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, the top American ace of World War I. “This notion was quickly lost after the first glimpse one had of Quentin.

“Gay, hearty and absolutely square in everything he said or did, Quentin Roosevelt was one of the most popular fellows in the group. We loved him purely for his own natural self,” Rickenbacker remembered.

Quentin Roosevelt was the fifth child of Teddy and Edith Roosevelt. Quentin was his father’s favorite, and his dad told stories to reporters about Quentin and the gang of boys -- sons of White House employees -- with whom he played.

When the United States entered World War I, Quentin Roosevelt was a Harvard student.

His father had argued for American entry into the war, so it was only natural for Quentin and the other three Roosevelt sons to join the military.

Quentin dropped out of Harvard and joined the 1st Aero Company of the New York National Guard. The unit trained at a local airfield on Long Island, which was later renamed Roosevelt Field in Quentin Roosevelt’s honor.

The 1st Aero Company was federalized in June 1917 as the 1st Reserve Aero Squadron and sent to France. Roosevelt went along and was assigned as a supply officer at a training base.

He learned to fly the Nieuport 28 that the French had provided to the Americans. The Nieuport 28 was a light biplane fighter armed with two Vickers machine gun.

The French had decided to outfit their fighter squadrons with the better SPAD 13 fighter, so the Nieuports were available for the Americans. They equipped the 95th and three other American fighter squadrons.

In June 1918, Roosevelt joined the 95th. Roosevelt was a good pilot but gained a reputation for being a risk-taker. With four weeks of training, Roosevelt got into the fight in July 1918.

On July 5, 1918, he was in combat twice.

On his first mission, the engine of Roosevelt’s Nieuport malfunctioned. A German fighter shot at him but missed. Later that day, he took up another plane, and the machine guns jammed.

On July 9, he shot down a German plane and may have got another.

On July 14, Bastille Day, the other American pilots were ordered into the air as part of the American effort to stop the German advance in what became known as the Second Battle of the Marne. The German Army was attacking toward Paris. The American Army was in their way.

In World War I, the main enemy air threat was observation planes that found targets for artillery. The job for Roosevelt and the other American pilots was to escort observation planes over German lines.

The Americans accomplished their mission and were heading home when they were jumped by at least seven German planes. The weather was cloudy, so Lt. Edward Buford, the flight leader, decided to break off and retreat.

But instead, he saw one American plane, engaging three German aircraft.

“I shook the two I was maneuvering with, and tried to get over to him but before I could reach him, his machine turned over on its back and plunged down and out of control,” Buford said.

“At the time of the fight, I did not know who the pilot was I’d seen go down,'' Buford remembered. “But as Quentin did not come back, it must have been him.

" His loss was one of the severest blows we have ever had in the squadron. He certainly died fighting,” Buford wrote.

Three German pilots took credit for downing Roosevelt. Most historians give credit to Sgt. Carl-Emil Graper. Roosevelt, Graper wrote later, fought courageously.

The Germans were shocked to find out they had killed the son of an American president.

On July 15, they buried Quentin Roosevelt with military honors where his plane crashed outside the village of Chamery. A thousand German soldiers paid their respects, according to an American prisoner of war who watched.

On the cross they erected, the German soldiers wrote: “Lieutenant Roosevelt, buried by the Germans.”

When the Germans retreated and the Allies retook Chamery, Roosevelt’s grave became a tourist attraction. Soldiers visited his grave, had their photograph taken there and took pieces of his Nieuport as souvenirs.

The commander of New York’s 69th Infantry, Col. Frank McCoy, had served as President Roosevelt’s military aid and had known Quentin when he was a boy. At McCoy’s direction, the regiment’s chaplain, Father (Capt.) Francis Duffy, had a cross made and put it in place at the grave.

“The plot had already been ornamented with a rustic fence by the Soldiers of the 32nd Division. We erected our own little monument without molesting the one that had been left by the Germans,” he wrote in his memoirs.

“It is fitting that enemy and friend alike should pay tribute to his heroism,” Duffy added.

An Army Signal Corps photographer and movie cameraman recorded the event.

After the war, the temporary grave stone was replaced with a permanent one, and Edith Roosevelt gave a fountain to the village of Chamery in memory of her son.

Roosevelt’s body remained where he fell until 1955. Then, at the request of the Roosevelt family, Quentin’s remains were exhumed.

He was laid to rest next to another son of Teddy Roosevelt; Theodore Roosevelt Jr. Ted, as he was called, was a brigadier general in the Army who led the men of the 4th Infantry Division ashore on Utah Beach on D-Day before dying of a heart attack on July 12, 1944.

Both men are buried in the Omaha Beach American Cemetery.

Quentin’s death shocked the apparently unstoppable Theodore Roosevelt Sr., who grieved deeply, according to his biographers.

Teddy Roosevelt had fought childhood asthma, coped with the deaths of his first wife and mother on the same day, started down rustlers as a rancher in the Dakotas, faced enemy fire in the Spanish-American War, survived a shooting attempt in 1912 and survived tropical illness and exhaustion during a 1914 expedition in the Amazon.

But six months after Quentin’s death, Theodore Roosevelt died of a heart attack in his sleep.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.