On Jan. 10, 1968, Private 1st Class Clarence Sasser was part of a reconnaissance mission in southern Vietnam when his detachment’s helicopters were attacked upon landing. Over five grueling hours, Sasser, an Army medic, risked his life to help his fellow soldiers to safety and aid the wounded despite leg and shoulder injuries that rendered him "in agonizing pain and faint from loss of blood."

The following year, President Richard Nixon presented Sasser with the Medal of Honor.

"I don't think what I did was above and beyond," Sasser, now 76, said during a video interview with the Congressional Medal of Honor Society (CMOHS) in the early 2000s. "I never have, and for a long time, I had a problem with that. But finally, ... a friend helped me reconcile it to the point that it meant, 'Hey, you did your job.'"

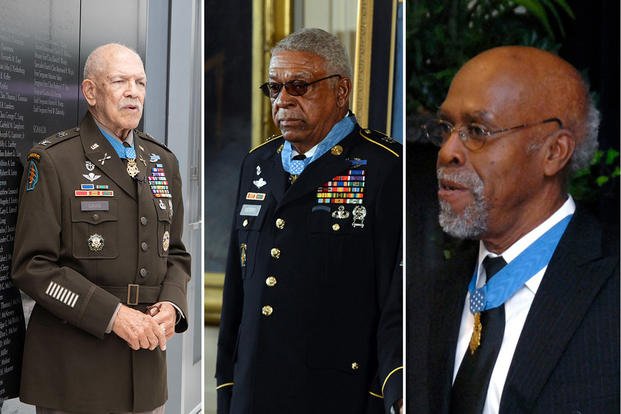

Fellow Vietnam War veterans Melvin Morris and Paris Davis did their jobs, too, and they eventually were rewarded with the U.S. military's highest award for valor after racism-fueled delays stretching generations. Davis, Morris and Sasser are the only three living Black Medal of Honor recipients, according to the CMOHS.

While Blacks have served in every major U.S. conflict dating to the Revolutionary War, only 94 have had their military service immortalized with a Medal of Honor, CMOHS data shows. Overall, 63 of the 3,517 Medal of Honor recipients all time are alive today.

"One of the good things about a war or any type of crisis like Vietnam is that ... there's no race there," Davis told talk-show host Phil Donahue in 1969, just after the civil rights movement in America ended. "In the dark, brown is just as Black or white as anyone else. They're bodies. They're human beings."

On June 17-18, 1965, Capt. Davis and three other Special Forces troops were assisting a regional force company from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or ARVN, near Bong Son when they were attacked. Over most of the next day, Davis was wounded multiple times, including having part of his trigger finger blown off, but repeatedly refused medical attention. Davis ignored a superior's order to stand down in order to retrieve three injured team members, and he helped guide inexperienced South Vietnamese soldiers as they staved off the Viet Cong until reinforcements arrived.

Davis' Medal of Honor nomination packet was inexplicably lost twice, and had it not been for an inspired group of advocates fervently promoting his case beginning in 2014, the Pentagon might not have finally ordered an expedited review three years ago. In 2023, President Joe Biden presented Davis with the award at the White House.

"You don't spend your life worrying about something that you have no control over," Davis, 84, said in a Washington Post article after his award ceremony. "You just let it happen the way it's going to happen."

Morris' White House ceremony came in 2014, nearly 4½ decades after he commanded a Special Forces unit near Chi Lang that came under surprise attack on Sept. 17, 1969. Then a staff sergeant, Morris reorganized his men before he and two others endured heavy fire while attempting to recover a dead team commander's body near an enemy bunker.

The men with Morris were injured, and after making sure they were safely back with friendly forces, Morris ventured forth once more with a couple of fresh volunteers as suppressive fire covered them. He successfully retrieved the dead master sergeant, whose map case containing sensitive information had fallen out of his pocket along the way.

Once again, Morris went back to grab the case, taking out four enemy bunkers with hand grenades as he endured intense machine-gun fire. He was wounded three times, including being shot at such close range that he saw bubbles coming out of his chest.

“With three bullet holes, I didn’t feel the pain,” Morris, 82, told the CMOHS in a video interview. “I [didn’t] feel nothing.”

Morris, who was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, was hospitalized for three months. The Medal of Honor would come much, much later.

“You’re happy. You’re glad. You’re nervous,” Morris, who went on to serve a second tour in Vietnam, said of receiving the award. “You’ve got a lot of anxiety; all of those things just come up. And I just became very proud. I don’t know, it just seemed like a weight was lifted off of me or something.”

No medal, though, can bring back what was lost on those battlefields or ease the painful memories of what Morris, Davis and Sasser saw and experienced. Sasser saved more than a dozen lives, according to author Larry Smith's 2003 book, "Beyond Glory: Medal of Honor Heroes in Their Own Words," but when he thinks back, he recalls “the thoroughly bad situation” confronted by his company, the intense sensation of how a shell fragment felt on his skin, his legs becoming immobilized during the fighting and, perhaps most of all, wounded service members pleading for their mothers’ comfort.

“‘Help me,’” Sasser, choking back tears, recalled the soldiers saying in the Congressional Medal of Honor Society interview. “There’s nothing I can do.”

Davis, who achieved the rank of colonel, considers the Medal of Honor a symbol of "what teamwork, service and dedication can achieve." As he prepared to receive his long-overdue award last year, Biden expressed the appreciation of a grateful nation, then addressed the former Green Beret directly.

"You are everything this medal means," Biden said. "I mean, everything this medal means."

The president's comments were meant for one man, but could have easily been said of any other Medal of Honor honoree, a very select club bonded by a common trait that any service member or civilian can understand: They did their job exceptionally well.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.