Augusto Giacoman served as an infantry officer with 1/5 Infantry and 1/2 Stryker Cavalry, deploying twice to Iraq in 2005, and 2007-2008. He currently works at the management consultancy Strategy&, and is chairperson of the board at Service to School, a nonprofit helping veterans achieve their educational goals.

We had a sniper problem.

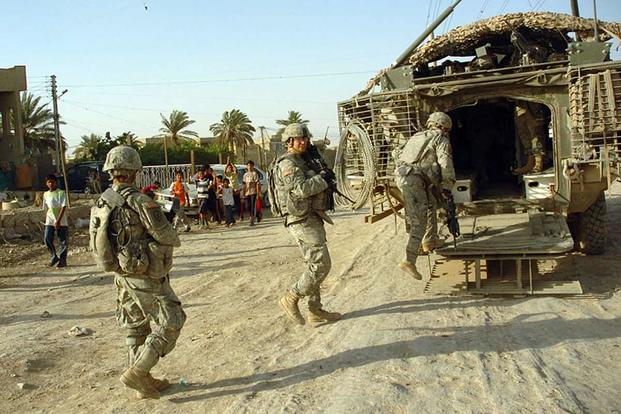

Our unit was building a wall that cut off North Sadr City, Iraq, and would deny the Mahdi Army Special Groups fighters the ability to fire rockets into the green zone. Every night a fierce attack erupted at the wall as the enemy converged on our main effort. But our massive firepower, including Apache helicopters, Abrams tanks, and Stryker infantry on the ground, killed dozens, repelling attack after attack and destroying the main force of the enemy. As they lost strength, they reverted to their tried-and-true guerrilla tactics, including snipers. Most weren’t a problem, but two incidents indicated one sniper in particular was very well armed and very well trained.

First he put a special, high-caliber bullet through the engine block of a high-ranking officer’s MRAP—a highly armored vehicle. It was so armored that normal bullets could not have penetrated the armor—much less go deep enough to kill an engine. The vehicle stopped dead cold and we had to scramble units to make sure we recovered the MRAP rapidly without any casualties.

The second incident happened a few nights later at the wall. Building the wall required us to become a construction crew. I would watch through a drone feed, or from the roof, as two-ton army trucks would bring seven-ton concrete barriers from the nearest forward operating base in Taji, Iraq. At 12 feet tall, roughly 6 feet wide, and a foot thick, they were massive, bulky barriers. Heavy machinery teams would use a long crane to get the barrier off the truck and place it on the road. Then, infantrymen or an engineer would scramble up ladders to the top of the barrier and link it through metal hoops and chains to the next barrier.

I was a battle captain, monitoring this construction at night—each soldier going up exposing himself to shots from the enemy. He’d grip the thin metal of the ladder as his stomach clenched, wondering if this climb would be his last. Then he’d hook the barriers together, climb down, and move the wobbly ladder over a barrier. Then the next soldier would go up. They’d switch back and forth all night long, continuously anxious, fearful, and alert. Every now and then they’d hear the insect whizz of a bullet. They knew they were being watched by the enemy. While we had support overlooking their position, they knew at any moment mortars may rain down on them, a grenade or an RPG may fly from an alley. All night long they managed their fear and all night long they built the wall, six feet at a time. All night long they hoped they would work six feet across and not end up six feet under.

It took a different sort of courage from a raid; those need a fast plunge—like a leap out of an airplane or a dive into a bungee jump. This courage was the boring sort—the kind that would reap no great glory or make up any great story. It was like the patina on an old gold ring. It looked dull but underneath was some of the most precious stuff there is.

So I watched the wall being built while also coordinating the engineers, infantry, armor, and air assets, like helicopters, in sector. One night, I watched a live drone feed as an Army truck brought the barriers down the road. The truck crossed a street, then sped up wildly heading far out of range of our protective units. I tried to raise the truck on the radio but they were not answering, just racing down the street. If they kept going, soon they would be in no man’s land, where the enemy could mass platoon-size forces quickly and capture or kill them.

I called the Stryker platoon in sector to get that truck to stop driving and respond to the radio. After a few tense minutes, the Stryker platoon flagged the truck down, before they could get further into danger.

The Stryker platoon leader told me that the driver of the truck had been shot. The platoon leader said, “Sir, you are not going to believe this, but the guy took a round to the helmet. It grazed across the helmet of the passenger and lodged into the driver’s helmet. He’s fine but he’s really freaking out; we are gonna send him back to get a replacement and get checked out.” As the platoon leader got the truck driver to calm down, I thought about the shot that hit the driver.

The army trucks were heavily up-armored—armor that would stop almost all rounds. The only place that wasn’t as up-armored was about a 2- to 3-inch section from the top of the door to the roof of the vehicle. The marksman had to have put a round in that 2- to 3-inch section from very far away. I knew we were dealing with a well-trained sniper.

The driver was unharmed but we took his helmet away, bullet still lodged in it, and sent it to our higher intelligence to analyze. A day or so later two counter-sniper SEAL teams were assigned to our unit. We briefed them on the couple of incidents and escorted them around Sadr City for a few days. I never found out if the enemy sniper had been killed or any other details on where he must have come from or his training, but one thing stands out: We stopped having sniper problems.

This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service, war, and its impact.

-- The opinions expressed in this op-ed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Military.com. If you would like to submit your own commentary, please send your article to opinions@military.com for consideration.