Retired Marine infantry officer Joe L'Etoile remembers when training money for his unit was so short "every man got four blanks; then we made butta-butta-bang noises" and "threw dirt clods for grenades."

Now, L'Etoile is director of the Defense Department's Close Combat Lethality Task Force and leading an effort to manage $2.5 billion worth of DoD investments into weapons, unmanned systems, body armor, training and promising new technology for a group that has typically ranked the lowest on the U.S. military's priority list: the grunts.

But the task force's mission isn't just about funding high-tech new equipment for Army, Marine and special operations close-combat forces. It is also digging into deeply entrenched policies and making changes to improve unit cohesion, leadership and even the methods used for selecting individuals who serve in close-combat formations.

Launched in February, the new joint task force is a top priority of Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, a retired Marine Corps infantry officer himself. With this level of potent support, L'Etoile is able to navigate through the bureaucratic strongholds of the Pentagon that traditionally favor large weapons programs such as Air Force fighters and Navy ships.

"This is a mechanism that resides at the OSD level, so it's fairly quick; we are fairly nimble," L'Etoile told Military.com on July 25. "And because this is the secretary's priority ... the bureaucracies respond well because the message is the secretary's."

Before he's done, L'Etoile said, the task force will "reinvent the way the squad is perceived within the department."

"I would like to see the squad viewed as a weapons platform and treated as such that its constituent parts matter," he said. "We would never put an aircraft onto the flight line that didn't have all of its parts, but a [Marine] squad that only has 10 out of 13? Yeah. Deploy it. Put it into combat. We need to take a look at what that costs us. And fundamentally, I believe down at my molecular level, we can do better."

Improving the Squad

Mattis' Feb. 8 memo to the service secretaries, Joint Chiefs of Staff and all combatant commands announcing the task force sent a shockwave through the force, stating "personnel policies, advances in training methods, and equipment have not kept pace with changes in available technology, human factors, science, and talent management best practices."

To L'Etoile, the task force is not out to fix what he describes as the U.S. military's "phenomenal" infantry and direct-action forces.

"Our charter is really just to take it to the next level," he said. "In terms of priorities, the material solution is not my number-one concern."

Gifted Grunts

For starters, the task force is looking at ways to identify Marines and soldiers who possess the characteristics and qualities that will make an infantry squad more efficient in the deadly art of close combat.

The concept is murky, but "we are investing in some leading-edge science to get at the question of what are the attributes to be successful in close combat and how do you screen for those attributes?" L'Etoile said. "How do you incentivize individuals with those attributes to come on board to the close-combat team, to stick their hand in the air for an infantry MOS?"

Col. Joey Polanco, the Army service lead at the task force, said it is evaluating several screening programs, some that rely on "big data and analytics to see if this individual would be a better fit for, say, infantry or close-combat formations."

Polanco, an infantry officer who has served in the 82nd Airborne and 10th Mountain divisions, said the task force is also looking at ways to incentivize these individuals to "want to continue to stay infantry."

L'Etoile said the task force is committed to changing policy to help fix a "wicked problem" in the Marine Corps of relying too heavily on corporals instead of sergeants to lead infantry squads.

"In the Marine Corps, there are plenty of squads that are being led by corporals instead of sergeants, and there are plenty of squads being led by lance corporals instead of corporals," he said. "I led infantry units in combat. There is a difference when a squad is led by a lance corporal -- no matter how stout his heart and back -- and a sergeant leading them."

Every Marine must be ready to take on leadership roles, but filling key leader jobs with junior enlisted personnel instead of sergeants degrades unit cohesion, L'Etoile said.

"When four guys are best buddies and they went to boot camp together and they go drinking beer together on the weekends ... and then one day the squad leader rotates and it's 'Hey Johnson, you are now the squad leader,' the human dynamics of that person becoming an effective leader with folks that were his peers is difficult to overcome," he said.

It's equally important to stabilize the squad's leadership so that "the squad leader doesn't show up three months before a deployment but is there in enough time to get that cohesion with his unit, his fire team leaders and his squad members," L'Etoile said. "Having the appropriate grade, age-experience level and training is really, really important."

The Army is compiling data to see if that issue is a persistent problem in its squads.

"When we get the data back, we will have a better idea of how do we increase the cohesion of an Army squad, and I think what you are going to find is, it needs its own solution, if there in fact is a problem," L'Etoile said.

No Budget, But Deep Pockets

Just weeks after the first U.S. combat forces went into Afghanistan in late 2001, the Army, Marine Corps and U.S. Special Operations Command began modernizing and upgrading individual and squad weapons and gear.

Since then, equipment officials have labored to field lighter body armor, more efficient load-bearing gear and new weapons to make infantry and special operations forces more lethal.

But the reality is, there is only so much money budgeted toward individual kit and weapons when other service priorities, such as armored vehicles and rotary-wing aircraft, need modernizing as well.

The task force has the freedom to look at where the DoD is "investing its research dollars and render an opinion on whether those dollars are being well spent," L'Etoile said. "I have no money; I don't want money. I don't want to spend the next two years managing a budget. That takes a lot of time and energy.

"But I am very interested in where money goes. So, for instance, if there is a particular close-combat capability that I believe represents a substantive increase in survivability, lethality -- you name it -- for a close-combat formation, and I see that is not being funded at a meaningful level, step one is to ask why," he continued. "Let's get informed on the issue ... and then if it makes sense, go advocate for additional funding for that capability."

The task force currently has reprogramming or new funding requests worth up to $2.5 billion for high-tech equipment and training efforts that L'Etoile would not describe in detail.

"I have a number of things that are teed up ... it's premature for me to say," he said. "In broad categories, we have active requests for additional funding in sensing; think robots and [unmanned aerial systems]. We have requests for additional funding of munitions for training and additional tactical capabilities [and] additional funding for training adversaries, so you get a sparring partner as well as a heavy bag."

The task force is requesting additional money for advanced night-vision equipment and synthetic-training technologies. L'Etoile also confirmed that it helped fund the Army's $500 million effort to train and equip the majority of its active brigade combat teams to fight in large, subterranean complexes like those that exist in North Korea.

"We can go to the department and say, 'This is of such importance that I think the department should shine a light on it and invest in it,' " he said.

Endorsing Futuristic Kit

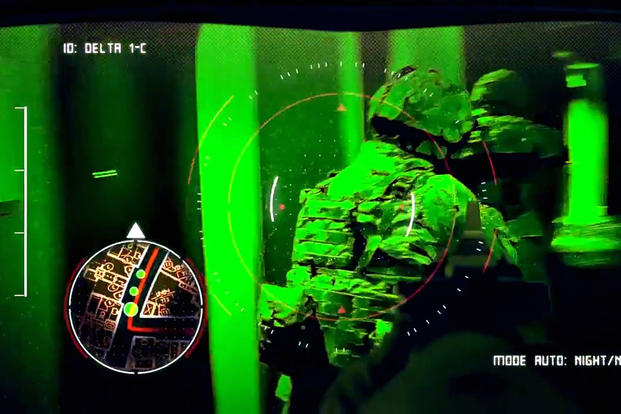

One example of this is the task force's interest in an Army program to equip its infantry units with a heads-up display designed to provide soldiers with a digital weapon-sight reticle, as well as tactical data about the immediate battlefield environment.

"The big thing is the Heads-Up Display 3.0. I would tell you that is one of the biggest things we are pushing," Polanco said. "It's focused primarily on helping us improve lethality, situational awareness, as well as our mobility."

The Army is currently working on HUD 1.0, which involves a thermal weapon sight mounted on the soldier's weapon that can wirelessly transmit the sight reticle into the new dual-tubed Enhanced Night Vision Goggle III B.

The system can also display waypoints and share information with other soldiers in the field, Army officials said.

The HUD 3.0 will draw on the synthetic training environment -- one of the Army's key priorities for modernizing training -- and allow soldiers to train and rehearse in a virtual training environment, as well as take into combat.

The service has already had soldiers test the HUD 1.0 version and provide feedback.

"If you look at the increased lethality just by taking that thermal reticle off of the weapon and putting it up into their eye, the testing has been off the chart," Brig. Gen. Christopher Donahue, director of the Army's Soldier Lethality Cross Functional Team, said at the Association of the United States Army's Global Force Symposium earlier this year.

The Army tried for years in the 1990s to accomplish this with its Land Warrior program, but it could be done only by running bulky cables from the weapon sight to the helmet-mounted display eyepiece. Soldiers found it too awkward and a snag hazard, so the effort was eventually shelved.

"Whatever we want to project up into that reticle -- that tube -- it's pretty easy," Donahue said. "It's just a matter of how you get it and how much data. We don't want too much information in there either ... we've got to figure that out."

The initial prototypes of the HUD 3.0 are scheduled to be ready in 18 months, he added.

"It is really a state-of-the art capability that allows you to train as you fight from a synthetic training environment standpoint to a live environment," Polanco said, adding that the task force has submitted a request to the DoD to find funding for the HUD 3.0.

"One of the things we have been able to do as a task force is we have endorsed and advocated strongly for this capability. ... It's going forward as a separate item that we are looking for funding on," he said.

Perhaps the biggest challenge before the task force is how to ensure all these efforts to make the squad more lethal will not be undone when Mattis is no longer in office.

"We ask ourselves every time we step up to the plate to take on one of these challenges, how do we make it enduring?" L'Etoile said.

"How do we ensure that the progress we make is not unwound when the priorities shift? So it's important when you take these things on that you are mindful that there ought to be an accompanying policy because ... they can't just get unwound overnight," he said.

-- Matthew Cox can be reached at matthew.cox@military.com.