As British ships sailed up Chesapeake Bay toward Washington, D.C., the leader of the capital city's militia expressed concern. But Secretary of War John Armstrong scoffed. "What the devil will they do here?" Armstrong said. "No! No! Baltimore is the place, sir. That is of so much more consequence." Armstrong assured President James Madison that there was no danger, so Madison wrote to his wife: "My dearest, I have passed among the troops who are in high spirits ... the last and probably best information is that [the enemy] are not very strong ... they are not in a condition to strike at Washington."

On Aug. 24, 1814, Armstrong and those who had not abandoned the young nation's capital city watched in horror as the Capitol burned and the British marched down Pennsylvania Avenue to the President's House. Shortly thereafter, Armstrong resigned.

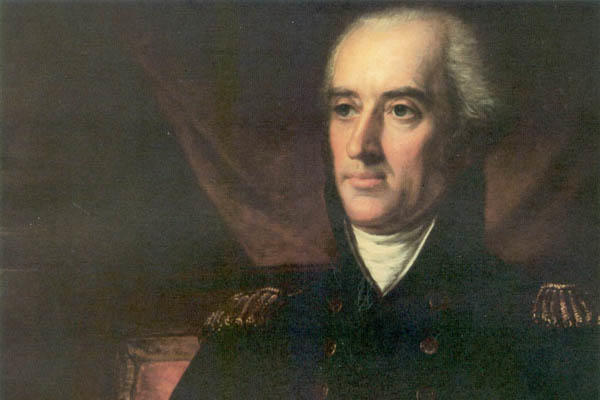

It had not been the only occasion on which Armstrong made a poor decision. The Pennsylvanian had attended The College of New Jersey (Princeton) but left to fight in the Revolutionary War, in which he was on the staff of Gen. Horatio Gates. In 1783, Armstrong wrote the anonymous "Newburgh Letters," urging Continental officers to agitate for salary arrears and other adjustments. Their commander in chief, Gen. George Washington, denounced these demands.

As Secretary of War, Armstrong believed it was his duty to direct soldiers in the field -- a belief that quickly soured most generals on him. In fact, Maj. Gen. William Henry Harrison resigned due to Armstrong's disregard for chain-of-command procedure. Armstrong replaced Harrison with militia general Andrew Jackson without asking for presidential approval, thereby angering Madison and earning himself a formal reprimand.

Despite these incidents, Armstrong, who had been appointed a brigadier general at the outset of the War of 1812, served the Army well in one respect: He oversaw the first edition of "Rules and Regulations of the Army of the United States," which has been the model for all future editions.