"Tables about breast high had been erected upon which the screaming victims were having legs and arms cut off. The surgeons and their assistants, stripped to the waist and bespattered with blood, stood around, some holding the poor fellows while others, armed with long, bloody knives and saws, cut and sawed away with frightful rapidity, throwing the mangled limbs on a pile nearby as soon as removed." -- Lt. Col. W.W. Blackford, 1st Virginia Cavalry

Detonating artillery shells and the non-stop rattling of musketry menacingly rumbled in the distance, barely audible over the groans and agonizing cries of dying men as droves of new arrivals steadily flooded into the ordinary, single-family home that was now being utilized as a front-line field hospital. Horse-drawn ambulance carts packed full of trauma victims lined the driveway to a grisly facility that mashed together a barely-serviceable emergency room, operating room, and morgue into a painfully-typical three-bedroom house on the outskirts of Chattanooga, Tennessee, the hospital's overworked, exhausted nurses desperately trying to triage the wounded between those who are possibly treatable and those who aren't going to make it.

Outside the city walls the Union Army, pushed back to Chattanooga following their crushing defeat at Chickamauga, was making a desperate stand to hold the city against a massive Confederate counter-attack. 46,000 men of Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee were entrenched on the heights overlooking the critical strategic rail and communications center, with the Union forces backed up against the Tennessee River, but now a massive assault led by General George Thomas was rushing straight up a steep ridge, straight into hardened enemy positions that included 112 cannons, and were taking murderous fire from the enemy in an all-out attempt to smash the Confederates' defensive positions and break out of the siege. Those wounded soldiers lucky enough to find their way back to friendly lines found themselves here, in a stinking, unsterilized, makeshift hospital surrounded by malaria-infected men and saw-wielding surgeons practicing a particular brand of medicine that had more in common with medieval torture than anything resembling a modern-day visit to the pediatrician, their only consolation being a cup of cold water and the soothing voice of nurses trying to comfort them and ease their pain in some small way.

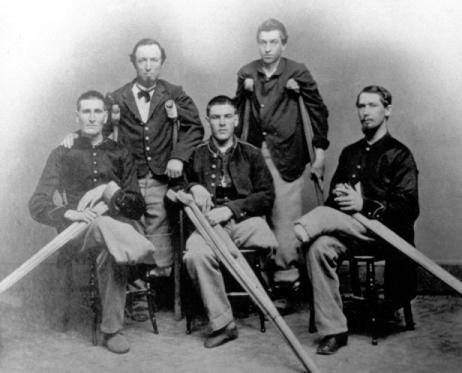

During the Civil War, over ten thousand women worked as nurses in field hospitals across the war zone.

Mary Edwards Walker of the 52nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry is the only one who served as a surgeon. She's also the only woman in history to ever receive the Medal of Honor, the highest award for military bravery offered by the United States of America.

Walker was a woman who was roughly a hundred and fifty years ahead of her time. Routinely criticized by women and men alike for her desire to wear men's clothing (at a time when "men's clothing" basically meant "any article of clothing that allowed you to walk through doorways or work in any capacity whatsoever), Walker paid her own way through Syracuse Medical College in 1855, becoming just the second woman in American history to complete physician training and work as a doctor. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Walker had already been running her own private practice for six years, but even though there were just 86 licenses surgeons in the Union Army at the start of the hostilities she was still turned away by every recruiting officer she approached. Undeterred, the 29 year-old surgeon signed on as a volunteer nurse, working on the front lines at the First Battle of Bull Run, then working as an unpaid volunteer surgeon at Indiana Hospital later that year.

Walker continued her practice of "I'll just show up wherever people are dying and see if they'll maybe let me help fix them for free", volunteering at the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862, performing front-line operations, and taking control of a medical train that was ferrying wounded men back to Washington. Her skills at slicing and dicing men up in the name of science so impressed Union General Ambrose Burnside that the Federal commander nominated her for a commission. At first she met with the resistance she was so used to encountering, but thanks to Burnside's recommendation, she was finally commissioned as an Assistant Surgeon in the 52nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, issued a U.S. Army surgeon's uniform, and sent to Tennessee to help treat wounded and dying men during the siege of Chattanooga. She would be the only woman in the war to receive this honor.

Now, in order to fully appreciate how intense the job of a Civil War surgeon actually was, try to think of it as something of a cross between the Spanish Inquisition and an Eastern European butcher shop. Since artillery shells, canister fire, and cannonballs typically resulted in the instant, untreatable, and horrific death of anyone unlucky enough to be standing in front of a cannon muzzle, the majority of Civil War surgical cases were from gunshot wounds caused by a .58-caliber minie ball – a soft metal, mostly hollow, incredibly heavy projectile over half an inch in diameter that was shaped very much like a modern bullet, and one that not only hit so hard that any bone it came in contact with shattered like a fluorescent lightbulb being smacked against a brick wall, but that also mushroomed on impact much like a modern-day hollow-point bullet, expanding to about an inch in width, ripping through muscle, blood vessels, organs, and all of those other important things that people keep inside their skin.

Because there was no such thing as organ transplantation, internal surgery, or blood transfusions, if a soldier got hit in the head, chest, or abdomen, he had a 90% chance of death – all you could do for the poor bastard was give him morphine and water and find a shady tree for him to sit under until he died. Wounds to the arms and legs had better odds, however, which is why fully three-quarters of surgeries performed during the war were amputations performed on these appendages.

With this:

Here's how it worked. After a guy got shot, he had 48 hours to get his arm cut off with an unsterilized hacksaw or he was probably going to die a painful death from gangrene. You, as the doctor, working in terrible conditions at someone's kitchen counter, would slosh the blood off the operating table with a bucket, get the guy up there, then you'd have a couple minutes to figure out what kind of shape he was in. If his arm wasn't broken, he might be ok – you can just wash it out, slap a tourniquet on there, and move on to the next guy. If it was broken, you'd need to operate. One of your nurses would anesthetize the dude with a chloroform-soaked rag (if it was available – in some field hospitals all you got was a shot of whiskey and a bullet to bite down on) until he was unconscious, then you'd have to stitch the broken artery closed with a needle and thread, dig the bullet out of there with your forceps, cut through the muscle with a sharp knife, saw through the bone with your hacksaw, tie off the arteries with another piece of thread, and then sew it all shut into a stump.

A good surgeon could perform the operation in under ten minutes. And he'd do it dozens of times in a row, all of this while people were pounding the city with artillery shells and stray bullets were slamming into the walls around them. One nurse at the Battle of Antietam recalled working on a guy in the hospital tent and then having a stray bullet pass through the tent, through the sleeve of her dress, and then kill him right in front of her, which, honestly may have been more of a humane way to go – because this was back before we knew you had to sterilize your equipment before you operated on a patient, almost 25% of people who underwent amputation surgery ended up dying from infected wounds.

Saving human lives by performing barbaric work with her bone saw under hellish conditions in the middle of a raging war zone as bullets and artillery shrapnel ripped through the skies around her, Mary Edwards Walker continued working as a front-line surgeon throughout the three-day Battle of Chattanooga. After a heroic, unlikely charge by George Thomas's men broke the Confederate position and sent Bragg retreating back to Georgia, Walker continued her work, not only assisting wounded Federal troops but also crossing enemy lines and providing medical care to Confederate troops and civilians in Tennessee and Georgia.

On one of these trips to Georgia to aid sick and injured civilians, Walker was ambushed by Confederate pickets, who found her in her Union uniform carrying two pistols and arrested her as a spy, a detail that may or may not actually have been true (we can't prove it either way). Her captors, who noted in their report that she argued "enough for a regiment of men", recommended sending her to a lunatic asylum for being a woman doctor, but instead she was sent to Richmond and thrown in a jail for Federal prisoners of war. She spent four months in brutal conditions in the POW Camp, Walker was sent back to Yankee lines as part of a prisoner exchange (she later confessed that she was very proud to have been traded straight-up for a male Confederate surgeon).

After the war, Walker was sent back to the Union Army, where she was attached to Sherman's army during the Atlanta Campaign. After the Battle of Atlanta, she was appointed Chief Surgeon at a women's military prison in Louisville, Kentucky, where she served until the end of the war. After her service, Walker collected an Army pension, wrote a couple books, became a women's suffrage activist, founded a weird commune, and got arrested a couple times for wearing pants instead of a dress.

During her time in the Union Army, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker had been recommended for promotion both by General George Thomas and by General William Tecumseh Sherman. Since she technically wasn't a uniformed service member, these requests for promotion could not be granted, but in honor of her service Mary Edwards Walker was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1866. Of the 1.8 million women who have served the United States military, she is the only one to ever receive the award. The Federal government tried to correct this in 1917 when they changed the guidelines for the Medal of Honor, stipulating that it could only be awarded for actions that occurred in combat, and stripped 900 people – including Dr. Walker – of their awards. Walker, obviously, told them to get bent – she wore the medal until her death in 1919. It was officially reinstated by order of the President in 1977.

|

|

Links:

National Institute of Health bio

Sources:

Bollett, Alfred J. "The Truth about Civil War Surgery." Civil War Times. June 12, 2006.

Davis, William. Civil War Journal. Thomas Nelson, 1999.

De Pauw, Linda Grant. Battle Cries and Lullabies. University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

Schroeder, Glenna R. The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine. M.E. Sharpe, 2008.

Wilbur, C. Keith. Civil War Medicine. Globe Pequot, 1998.